By John D. Stoll

BLACKSBURG, Va. -- It's been a choppy ride for many of the folks

relying on paychecks from Boeing Co. Slammed by the pandemic and

the grounding of its most important plane, the aerospace giant said

recently that it expects to end 2021 with 30,000 fewer workers than

it started this year.

"Decisions like these are not easy," Boeing Chief Executive

David Calhoun said on a webcast. These job cuts come as the airline

industry weathers an unprecedented travel drought and Boeing

endures a "year that is among the most difficult in our 100-year

history."

Even as Mr. Calhoun shows current employees the exit, he is

pushing forward a program at Virginia Tech, his alma mater,

designed to better prepare the next-generation's workforce to avoid

a similar fate.

An accountant by training, the 63-year-old executive recently

told me Corporate America mislabels what he calls a "discovery gap"

as the "skills gap." Colleges, he said, do a yeoman's job churning

out competent coders, scientists and engineers. Such skills are in

long supply. Where they fall short is teaching how to think outside

the cubicle or beyond the screen in front of them.

"We're now trying to solve for things outside just the raw

technology, and we have very few people who are really skilled at

doing that kind of thing," Mr. Calhoun said. Creating autonomous

planes that don't need a physical pilot in the cockpit (think

pilotless cargo aircraft or urban air taxis) or repairing flawed

product programs require as much understanding of how humans are

designed as machines are.

"Usually we are left on our own to develop that discovery

muscle, and we don't usually get these program or project leaders

-- the one or two who look like they are really good at that kind

of thing -- usually they are in their mid 40s or early 50s," he

said.

Virginia Tech's Honors College serves as the starting point for

Mr. Calhoun's crusade to churn out more competent thinkers at a

younger age.

He started the Calhoun Discovery Program with a $20 million gift

in 2018 when he was on Boeing's board and Boeing's problems with

the 737 MAX airliner had yet to turn the company upside down. The

program resembles a hands-on mixer for people with different

interests and ambitions in life, collaborating on projects that

require a multitude of approaches and specializations to complete.

The goal: teach students that problem-solving requires both sides

of the brain.

I visited the Calhoun program in October as dozens of freshmen

and sophomores with majors ranging from environmental policy to

industrial design to journalism clustered in groups. They were

discussing progress on real-world projects handed to them by active

employees at Boeing, General Electric Co. and Caterpillar Inc., and

overseen by professors from diverse disciplines.

Most students in the program are on campus, often working from

dorms or other locales that allow them to collaborate virtually.

But Virginia Tech is open for classes, and students often

congregate in workshops or areas where they can craft solutions and

test ideas in person.

One group of freshmen, working on a GE warehousing problem, had

drawn up a schematic to illustrate potential solutions. When I

asked for details, Claudia Budzyn, an environmental policy and

planning major, flipped around her laptop to show me how her team's

"Speedy System" worked. As I looked, the team talked me through the

complex web of sensors, data and checkpoints they created to hasten

the order-to-delivery process.

One student told me if GE is going to survive, it needs to think

more like Amazon and less like GE.

Mr. Calhoun checked in with Ms. Budzyn and dozens of her cohorts

in late October, just days before the latest jobs-cuts

announcement. He wanted to reassure them this somewhat

unconventional style of education is valuable.

"Our own team of very experienced engineers and Ph.D.s are

working on those exact same projects, trying to figure out how to

foolproof our system or create opportunities in our businesses," he

said during a 30-minute Zoom call that I listened in on. He

concluded by saying his time spent with students is among his

favorite memories in recent months.

"You're working on real things -- these are not little

projects," he said. He's given similar talks to sophomores who are

in the second year of this program, which was established in

2019.

Sydney Szabos, an 18-year-old engineering major focused on

electrical applications, told me the message took root.

She devotes countless hours to solving riddles the program

throws at her, in addition to her other classes outside of it. Few

of those riddles are solved without the help of

non-engineering-minded colleagues.

Under the guidance of experts from Caterpillar, Ms. Szabos and a

team of classmates currently are trying to figure out how to

program drones to inspect autonomous mining equipment stationed in

remote locations.

Ms. Szabos explained to me why computer-aided design renderings

are more efficient than global positioning systems and less

expensive than lidar technologies to guide drones. (Lidar is the

gadgetry seen on the roofs of autonomous test cars, using laser

light and other technology to judge distances.) One of her

classmates told me they think it may be possible to dock and

recharge these drones on the mining equipment.

All of this is trial-and-error at this point. Student teams

check in often on Zoom calls with working professionals to refine

their plan or change course.

I asked Ms. Szabos how this differs from core engineering

courses. "We're making paper airplanes in one of them," she said. I

thought it was a joke until she walked me through how making a

perfect paper airplane is an essential building block for the

discipline.

"It's just a different way of learning," she said. "There, we're

starting smaller and working our way up. Here, we start big and

stay big."

Why?

Charles "Chip" Blankenship, an adjunct professor at Virginia

Tech who worked with Mr. Calhoun at GE's aviation business years

ago, said companies have long encouraged single-minded focus on

business problems.

When he was running GE's appliance business he said the focus

could be so heavily skewed toward hitting financial targets, or

winning regulatory approval on a near-term project, or perfecting

the technology on the next product launch, that staffers failed to

consider the bigger picture. That unit was eventually sold off.

"You need that short-term focus, of course," he said. "But a big

part of your organization needs to spend their time looking around

corners." Those who haven't "flexed the discovery muscle" (one of

Mr. Calhoun's favorite sayings) by leveraging multiple fields of

study while trying to problem solve don't know what corners to look

around.

As Boeing, for instance, tries to tackle autonomous airplanes,

Mr. Calhoun said solving the technology isn't the problem. "Our

problem is going to be how do you get a regulator to allow for or

provide for air traffic over a given city. You're going to have to

understand the political-science consequences" to make that

happen.

For D'Arrin Calloway, that kind of cross-pollination was what he

was looking for coming out of Lynchburg, Va.'s Heritage High School

in 2019, but didn't know how to pursue. He applied to 40 schools

and was accepted to many. Virginia Tech wasn't high on the list

until he visited an open house and found out about this program and

heard Mr. Calhoun's pitch.

"I was pretty sold from then on," Mr. Calloway said. One of the

important keywords he heard was "collaboration" and the promise of

meeting students from various backgrounds and interests -- an

experience he felt was lacking in his hometown.

Mr. Calloway's interests are broad. He applied to several

engineering schools, but then considered a double major in real

estate and finance at Virginia Tech. The Calhoun program introduced

him to the field of business information technology, which appealed

to his entrepreneurial spirit.

Now a sophomore, the 19-year-old Mr. Calloway has worked on

college-diversity projects, built a website, learned the art of

video editing and conducted analysis on regional incentives for

energy infrastructure.

"My major has nothing to do with a lot of these things, and I

was never expecting to do classes like these," he said. "It changes

the way I approach every project."

Write to John D. Stoll at john.stoll@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

November 13, 2020 11:18 ET (16:18 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

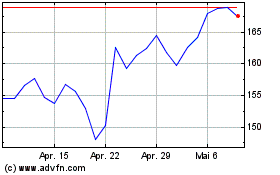

GE Aerospace (NYSE:GE)

Historical Stock Chart

Von Apr 2024 bis Mai 2024

GE Aerospace (NYSE:GE)

Historical Stock Chart

Von Mai 2023 bis Mai 2024