By David Benoit And Jacob Bunge

Shortly after Edward Breen stepped in to run DuPont Co. in

October, Andrew Liveris, longtime head of Dow Chemical Co., called

with a proposal.

Mr. Liveris saw an opportunity to strike the merger he had long

wanted, marrying the two giants of American industry with a

combined market capitalization of more than $130 billion, and he

was eager to talk to the noted deal maker now leading his

rival.

Mr. Breen asked for some time. He later joked with bankers that

he hadn't even had a chance to find the bathrooms at DuPont when

Mr. Liveris came calling, according to people familiar with the

matter.

Nine weeks later, Dow and DuPont are on the verge of

consummating a deal. The two are in advanced talks on a merger that

would reshape the chemical and agricultural industries by creating

a new massive company, which would quickly be spun into three

entities, The Wall Street Journal reported Tuesday. A deal could be

announced as soon as this week.

It comes at a time of sinking commodity prices and a

strengthening U.S. dollar, which have hurt revenues across the

companies' business lines. Both companies have shed some of their

hallmark businesses that generated lower profits and left them

exposed to price swings, while focusing on proprietary products in

faster-growing sectors such as food, electronics and packaging.

Dow and DuPont also have cut costs and streamlined operations,

but both drew critiques from activist investors-- Nelson Peltz's

Trian Fund Management LP at DuPont and Daniel Loeb's Third Point

LLC at Dow--who said executives moved too slowly and that the

companies were still too big and losing ground to nimbler

competitors.

By combining and then breaking up, DuPont and Dow see a way to

speed the process in one fell swoop, while creating an agricultural

giant and a materials maker that could each be worth more than the

current stand-alone companies, according to the people familiar

with the talks.

Agriculture would account for 23% of Dow and DuPont's combined

revenue; performance materials and chemicals 48%; and other

divisions, like nutrition and consumer products, would make up 29%.

The companies in 2014 generated $93.2 billion in combined

sales.

Shareholders cheered the idea on Wednesday, sending both

companies' stocks up 12%, adding a combined $14 billion in market

value. Dow gained $6.07 to $56.97, while DuPont gained $7.89 to

$74.49--the largest dollar gains for each since at least 1972.

Mr. Liveris has been pushing for a deal for much of his 11-year

tenure at Dow, the world's second-biggest chemical manufacturer. He

has bet the Midland, Mich., company's future on material-sciences

products used in industrial, automotive and construction sectors

that come with high prices that are less tied to underlying

commodities.

To do that, he needs to reduce Dow's exposure to agriculture

sciences that make seeds and various other chemicals based on

petroleum products.

DuPont, in Wilmington, Del., was facing similar pressures and

looking to also boost margins and reduce the cyclical nature of its

business. It started growing its agricultural businesses, sold its

paints business and spun off a performance-chemicals business.

Mr. Liveris had tried to strike a deal before, attempting to buy

DuPont in 2006, people familiar with the matter said. When that

went nowhere, Mr. Liveris acquired specialty chemicals producer

Rohm & Haas Chemicals LLC in 2009, a $16 billion deal struck

just as the market for financing collapsed.

The deal nearly fell apart, and the debt burden forced Mr.

Liveris to break a pledge to never cut Dow's dividend and to take a

$3 billion rescue financing package from Warren Buffett.

Mr. Liveris tried repeatedly to get DuPont to come to the table,

the people said. He engaged in talks with Ellen Kullman, who took

over DuPont in 2009, they said, but the talks never amounted to a

deal.

Ms. Kullman's tenure ended abruptly this October. She had

survived a proxy fight with Trian, which had argued for a breakup

of agriculture and industrial products. Ms. Kullman won a close

shareholder vote in May partly by promising DuPont would hit

earnings targets.

But when DuPont's earnings failed to turn around and shares fell

for months after DuPont's annual meeting, Ms. Kullman announced she

would retire. Mr. Breen, a noted turnaround artist who broke up

Tyco International PLC and created large shareholder returns there,

was named DuPont's interim chief executive.

The change set off a round of talks among those in the

agricultural industry. Already St. Louis-based Monsanto Co. had

sought to acquire Syngenta AG for $46 billion--an idea the Swiss

company rejected. Messrs. Breen and Liveris both publicly declared

they would entertain deals.

After Mr. Breen found his bearings at DuPont, the two executives

began talking about their entire companies, not just the

agriculture units. Mr. Liveris presented the idea he thought would

bring the most value: A merger of equals followed quickly by a

breakup into an agricultural company and a materials company, the

people said.

Mr. Breen quickly saw the financial possibilities but suggested

a further split, with a third business for various specialty

chemical products like nutrition that didn't fit with the other

two, the people said.

The combined entity would allow them to rapidly cut some $3

billion in costs, and then spin out three specialized companies

that have differing research-and-development needs and can attract

different investors, the people said.

Breakups for those reasons have been in vogue in the U.S., as

activists pressure companies to sharpen their focus. The trend has

collided with a record year for mergers and acquisitions, with

Pfizer Inc. and Allergan PLC announcing a similar megamerger

followed by a plan to separate some assets.

Dow and DuPont believed the planned splits would alleviate

concerns about antitrust regulators blocking a deal, the people

said. Though the deal would create a company with high market share

in several businesses, the stand-alone entities would continue to

face stiff competition, the people said.

DuPont removed the interim tag from Mr. Breen's title on Nov. 9,

naming him officially chairman and chief executive.

Trian blessed the move, it had told the board before the

announcement, people familiar with the matter said. But it still

expected to see improved results and laid out a plan for him to get

there, the people said. Trian has supported the deal talks and

encouraged the DuPont board to reach an agreement, people familiar

with the matter said.

At the same time, Mr. Liveris and Dow were gearing up for their

own activist investor to re-emerge.

In January 2014, Mr. Loeb's Third Point had taken what was then

a $1.3 billion stake in the company and began calling for a split

of its petrochemical products, about two-thirds of Dow's revenue,

from specialty products, which includes agriculture, food,

pharmaceuticals and electronics. Mr. Loeb neared a proxy fight,

launching a website and a political-ad style video lambasting Mr.

Liveris for mismanagement. The sides settled quickly, with both

appointing two directors to the Dow board, and an agreement that

kept Mr. Loeb from speaking on Dow publicly for a year.

The activist's view on Mr. Liveris hasn't changed, and Mr. Loeb

was expected to call for a management change, people familiar with

the matter said. This weekend, that standstill expires.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

December 09, 2015 20:15 ET (01:15 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2015 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

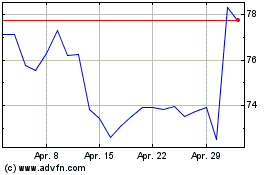

DuPont de Nemours (NYSE:DD)

Historical Stock Chart

Von Jun 2024 bis Jul 2024

DuPont de Nemours (NYSE:DD)

Historical Stock Chart

Von Jul 2023 bis Jul 2024