SCHEDULE 14A

Proxy Statement Pursuant to Section 14(a)

of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934

Filed by the Registrant ¨

Filed by a Party other than the Registrant þ

Check the appropriate box:

| ¨ |

Preliminary Proxy Statement |

| ¨ |

Confidential, for Use of the Commission Only (as permitted by Rule 14a-6(e)(2)) |

| ¨ |

Definitive Proxy Statement |

| þ |

Definitive Additional Materials |

| ¨ |

Soliciting Material Under Rule 14a-12 |

BlackRock New York Municipal Income Trust

(Name of Registrant as Specified In Its Charter)

Saba Capital Management, L.P.

(Name of Person(s) Filing Proxy Statement, if

other than the Registrant)

Payment of Filing Fee (Check all boxes that apply):

| ☑ |

No fee required. |

| |

|

| ¨ |

Fee paid previously with preliminary materials. |

| ¨ |

Fee computed on table in exhibit required by Item 25(b) per Exchange Act Rules 14a6(i)(1) and 0-11. |

Saba Capital Management, L.P. posted the materials in Exhibit 1

to https://www.heyblackrock.com/ (the “Website”). The Website contains links to certain articles, copies of which

are filed herewith as Exhibit 2. In addition, Boaz R. Weinstein (“Mr. Weinstein”) posted the messages attached hereto

as Exhibit 3 to his X account. One of the tweets in Exhibit 3 referred to Mr. Weinstein’s interview on CNBC’s

Squawk Box, the transcript of which is attached hereto as Exhibit 4. Attached as Exhibit 5 is an email sent to shareholders.

Exhibit

1

Exhibit

2

Boaz versus BlackRock: the fight over closed-end funds

Saba founder says he never planned to be an activist investor.

Now he’s battling BlackRock - again

In the spring of 2019, Boaz Weinstein’s Saba Capital bought

sizeable stakes in two BlackRock bond funds and nominated board candidates for both ahead of their annual meetings. Saba was pressing

BlackRock to tender shares in the funds, both of which were trading at a deep discount to net asset value. A tender at NAV would allow

the hedge fund to cash out with a return in the region of 14%.

After Saba submitted nomination notices for the annual meetings,

the BlackRock funds sent the firm a 47-page questionnaire about the nominees. Weinstein says Saba returned the completed questionnaire

within a week – but BlackRock refused to accept it, claiming the firm had missed the deadline.

“It was a ‘gotcha’ thing,” says Weinstein.

“The questionnaire had irrelevant questions like whether we’d violated the Iran nuclear sanctions laws.”

Saba took BlackRock to court over its filibustering questionnaire

and initially won. The court’s vice-chancellor said the request “went too far”, but an appellate court reversed the

ruling. Then in June 2020, a year into the dispute, BlackRock announced it would merge the closed-end funds into existing open-ended vehicles

after all.

“Thousands of mom-and-pop investors got to exit at NAV and

that was great,” Weinstein says. Saba, of course, made its money too.

But Weinstein didn’t stop there. Since then, he has picked

a fresh fight with BlackRock over three other funds it manages. And he’s promising more drama. “Big potatoes, not small potatoes.”

Closed-end fund arbitrage – the strategy Saba is pursuing

– is a realm of public relations tactics, court battles and fighting talk. Weinstein says he never set out to be part of this world.

Now, though, he’s all in.

Saba has become the biggest player in the space in recent years,

with $3 billion invested. A source with knowledge of the matter says the firm is raising money for expansion, with ambitions to perhaps

double its positions in closed-end funds in a year. Weinstein has already deployed over half a billion dollars in the UK.

For now, arguably the biggest potato on Weinstein’s plate

is the BlackRock Innovation and Growth Term Trust (BIGZ), which went public in March 2021 at $20 a share, raising $5 billion. Now it trades

at less than $8 a share. “They literally lit $3.3 billion dollars on fire,” Weinstein says. “If the holders had instead

been in the Nasdaq, they’d have made 4%, not lost 52%.”

BIGZ has “given people the Cathie Wood 2021 drawdown with

none of the Cathie Wood pre-2021 love,” he says, referring to the founder of Ark Invest whose tech-flavoured flagship fund has lost

around three-quarters of its value. “Adding insult to injury there is also $300 million of trapped discount. And we are coming up

the ranks on it.” Saba has a $130 million position.

Saba is seeking seats on the board and is pressing BIGZ to tender

at least a tenth of its shares each quarter “at or close to NAV” if the average daily discount runs higher than 10%.

You can’t disenfranchise shareholders. You can’t entrench

yourself. You can’t set an impossible voting standard

Boaz Weinstein

Weinstein’s hedge fund has also built a $200 million position

in BlackRock’s ESG Capital Allocation Term Trust, which trades at a discount of 11% after reaching as low as 20% following its launch

only 20 months ago.

To the end of May, ECAT had returned -13% since launch.

The third fund, BlackRock California Municipal Income Trust (BFZ),

trades at a discount of 8%. Saba owns just under $50 million, about 14% of the outstanding shares.

With the proxy campaign heating up, Weinstein is accusing BlackRock

of disregarding its own stated principles of good corporate governance.

ECAT, like BIGZ, requires a voting majority of all shares to secure

board positions in contested elections. That makes it effectively impossible for challengers to secure seats, Saba argues. Normally only

about 60% of shares are voted in such ballots.

“We can show you the part of their ESG bible where they say

‘thou shalt not do this’,” Weinstein says. “And they’re doing it to everyone… in an ESG fund….

It makes your head explode. On this one I have a real bone to pick with them. I’m buying more.”

BlackRock’s guidelines state that majority voting is preferable

in uncontested elections but “may not be appropriate in all circumstances”, such as contested elections.

BlackRock is in belligerent mood too. In an emailed statement, a

spokesperson says: “Saba’s interest is short-term profit – not governance. Its playbook uses the veil of governance

to disrupt the investment objectives and strategies of closed-end funds by seeking to force changes that enrich itself at the expense

of long-term shareholders.”

Shareholders will have their say on Saba’s proposals in July,

when BlackRock’s closed-end funds hold their annual meetings.

Jumbo shrimp

Saba’s proxy fights are playing out in what was a sleepy corner

of the industry. Some closed-end funds trace their history to the late 1920s when railway consolidation left firms like Adams Express,

now Adams Funds, with cash to invest.

Investors buy from a manager at IPO but can exit a fund only by

selling shares in the open market. For fans, the appeal is clear. Permanent capital allows the funds to employ greater leverage and invest

in less-liquid assets. Advocates emphasise the funds’ ability to pay out steady dividends. US closed-end funds delivered more than

6% on assets last year, according to data from the Investment Company Institute.

On the downside, though, shares often trade at a discount to NAV,

because of management fees or if sellers of a fund outnumber natural buyers. Substantial discounts are common. Fifteen percent of US closed-end

funds traded at a discount of more than 15% to NAV at the time of writing, data from Morningstar Direct shows.

Weinstein says the funds are “sold not bought”. Brokers

push the product at IPO, he argues. Afterwards, when the selling campaign cools, demand tails off.

Photo: Jerry Goldberg; BlacRock says Saba’s tactics continue

to “potentially endanger” the closed-end fund landscape

The arbitrage trade to be done, then, is to buy at a discount, hedge

exposure to the underlying assets and press the fund to liquidate or tender for part of its shares at something close to NAV.

Potential targets with discounts that make them interesting to a

firm like Saba amount to about $80 billion in assets under management. That’s from an industry worth over $450 billion across more

than 750 funds, Weinstein says.

In this niche activist area Saba is a big fish in a small pond –

or, in Weinstein’s words, a “jumbo shrimp”. The pond is widening, though. Just two years ago closed-end funds worth

only about $10 billion were trading at discounts of more than 15% and Saba had about $600 million in the strategy. Today that strategy

has grown to five times the previous size.

The source with knowledge of the matter says the firm’s dedicated

fund has about a 10% net return for the past eight years.

Too small for Buffett

Weinstein comes across as modest, even a little self-conscious.

His dark-wood panelled home office seems – through a Zoom lens at least – to be not much larger than a walk-in cupboard.

Those in the closed-end fund community would probably say the modesty

is false. But when Weinstein describes what first got him interested in these funds it seems real enough.

Between Saba Capital’s launch in 2009 and the middle of 2012,

the hedge fund had grown from $150 million to $5 billion. But during the next 12 months, Saba’s existing strategies – the

relative value trades in credit for which Weinstein is best known – lost money. A rethink was required.

“I’d been looking at other discount opportunities for

a while, even in esoteric corners of the market,” he says. That included, some years earlier, assessing discounts on Korean preferred

stock versus common stock. That trade had poor prospects of paying off, it turned out. “There has been a big discount for 20 years

and there may be a big discount for the next 20.”

Weinstein personally had owned closed-end funds in the early 2000s.

“I wasn’t a savvy investor. But I was savvy enough to read in Barron’s about a Morgan Stanley fund trading at a 30%

or 35% discount. So I had this personal experience investing in this product that is 85%-plus owned by individual investors.”

Then he recalls reading at the time of the taper tantrum about closed-end

funds trading at discounts. “It was a trade to buy a bunch at a minus-nine discount to NAV that had been at a plus-one premium to

NAV, and it turned into a big business.”

The idea isn’t new. And Weinstein isn’t saying it is.

Warren Buffett pursued the same trade. Edward Thorp writes in detail about a successful closed-end strategy in his autobiography A Man

For All Markets. (Weinstein said at a Bloomberg conference recently that meeting Thorp was a bucket list item; the two have scheduled

a lunch later this year.)

Weinstein even corresponded with Buffett on the topic, after Buffett

said he wished Weinstein had shown him the London Whale bet back in 2012 and to bring him any such big opportunities in the future.

In an email exchange, Weinstein shared the closed-end funds idea

with Buffett, but it was too small for Berkshire Hathaway. Buffett did send Weinstein, though, a PDF of yellowed sheets of paper from

1950 showing Buffett’s holdings at the time, of which two were discounted closed-end funds.

Advantage player

Weinstein and activist investing seem a peculiar match. A titled

chess player in his teens, he’s known for cool-headedly summing odds more than picking arguments.

A quote from Puggy Pearson, the professional poker player and world

series winner, is a favourite. “Ain’t only three things to gambling: knowing the 60-40 end of the proposition, money management,

and knowing yourself.”

Then again, the odds in the closed-end fund trade may be uniquely

attractive.

And people that know him describe Weinstein as a so-called advantage

player, the type of gambler that likes to find ways within the rules to tilt the odds in their favour. He was associated with an MIT team

that famously used card-counting techniques to beat casinos in the 1990s.

Weinstein confesses to “being worried” when someone

on the other side of a trade might have fundamental knowledge he lacks. “Who in their right mind would think they can beat Citadel

or DE Shaw six times out of 10?”

He has always gravitated towards being “on the right side

of a mispricing that exists because of a technical”, he says. “The technical in closed-end funds is that retail wants to sell.”

Given his willingness to challenge Wall Street’s biggest operators,

though, does Weinstein see himself as a rebel, an outsider? This isn’t the first time he’s taken on the establishment, after

all. Weinstein’s London Whale trade in 2012 cost JP Morgan more than $6 billion.

He says not. He’s worked on Wall Street since interning at

Merrill Lynch aged 15, he points out. Instead, he says he considers himself an unconventional thinker.

Accidental activist

In fact, as Weinstein tells it, Saba made the step to activist investor

almost by chance.

In 2013 the firm was the biggest investor in two UBS closed-end

funds that were compelled to liquidate by another manager – Bulldog Investors, a firm that has long followed the activist strategy.

Saba was also mapping indentures from IPO documents for hundreds

of closed-end funds and came across a Deutsche Bank fund that was obligated to tender for shares if it traded at a big enough discount

for more than a quarter.

Weinstein and his colleagues realised the Deutsche fund was on track

to liquidate and Saba bought more shares, ultimately making about a 15% gain, according to a source with knowledge of the trade.

In the early campaigns, though, there were no proxy battles. The

approach was “gentle”, Weinstein says – asking funds to tender for a portion of shares at a one or two percent discount

to NAV.

We aren’t depriving investors of investment fund options and,

in any case, they’re swimming in [options] – between ETFs, mutual funds, closed-end funds and all the rest

Boaz Weinstein

Weinstein says he still prefers to avoid a fight if he can. It’s

easy to see why. A number of small, quick exchanges potentially deliver more profit to a firm like Saba than a big battle where the gains

might be greater, but the time expended longer.

That said, Saba’s approach has hardened more recently. “We

weren’t looking to make an example,” Weinstein says. “But somebody did something so outrageous that we took a much stiffer

stance.”

In 2020 all eight board members at the Voya Prime Rate Trust, managed

by Voya Investments, were up for election. Saba owned 22% of the shares. The fund was trading at an 18% discount.

Three months before the election, Voya announced that board seats

would in future require backing from a 60% majority of shares, rather than 50% of the votes cast.

Because of the low participation rates in such votes, the fund’s

new rule effectively blocked Saba’s chances of securing its nominations. “We took them to court,” Weinstein says. “You

can’t disenfranchise shareholders. You can’t entrench yourself. You can’t set an impossible voting standard.”

In June, a judge ordered Voya to abandon its proposed change, saying

the bylaw amendment effectively prevented any new trustees from being elected.

Saba put in its own board and then in June 2021 took over the management

of the fund itself. “It’s an opportunity for us to show the industry that these funds can be run better, that there’s

a right way to do it,” Weinstein says.

The Saba-run fund ranked as the best performing bond closed-end

fund in its latest financial year, to November 2022, according to the company’s own data.

Voya declined to speak to Risk.net for this article.

‘Mind blowing’

For sure, Weinstein is unafraid to ruffle feathers. Others in the

space welcome the muscular approach. “Going on Twitter and blasting BlackRock for essentially hypocrisy, I think it’s fair

game,” says Phillip Goldstein, Bulldog Investors’ co-founder. “They’ve done a lot of good work that’s helped

other shareholders.”

Another recent high-profile battle, this one versus Franklin Templeton

and its Templeton Global Income Fund, shows how acrimonious that work can become.

The Templeton fund and trustee Charles B Johnson III sought an injunction

to stop Saba seating its board after a successful campaign by the hedge fund in 2022. Templeton and Johnson argued Saba should have made

public sooner than it did a last-minute deal to acquire shares from two other activist funds, Bulldog Investors and Almitas Capital, ahead

of the vote.

“Franklin – having to face the reality of losing –

sued us,” says Weinstein. “They said there should be a redo of the election.”

In discovery, Saba found something Weinstein characterises as “mind

blowing”. Email exchanges between Franklin and the fund’s second biggest shareholder First Trust showed the two had communicated

about whether and when First Trust would fall below a 10% holding.

In court documents Saba accused Franklin of a co-ordinated effort

to mislead the hedge fund as to how First Trust would vote.

According to US law, a fund like First Trust would have to

vote its shares proportionally with other voters – so called mirror voting – if it held more than a 10% threshold. The

Templeton fund’s April 12 proxy statement listed First Trust as holding 11.22% of shares. Saba said Franklin knew the true

figure was below the threshold when it filed the proxy statement and was obligated to say so.

The fund countered that Saba did have information about the up-to-date

holdings of First Trust. But Saba says the shareholder disclosures in question are discretionary and therefore could not be taken as a

reliable record of positions.

A day before the appellate hearing the Templeton fund backed down

and Saba seated the board. Franklin Templeton declined to comment for this article.

A righteous cause

Weinstein insists the campaigns against the likes of Franklin Templeton,

Voya and BlackRock put him on the right side of right and wrong.

He makes a point of stating that most closed-end funds are “decent”

products, that many trade at a negligible discount and that “some” operators are conscientious.

Some closed-end funds use measures such as buy-backs to narrow discounts

when they become overly wide. The Goldman Sachs MLP and Energy Renaissance Fund announced in recent days a plan to liquidate voluntarily.

But then Weinstein speaks at length about what he sees as the bad

actors. “I don’t want to get ‘doing-God’s-work’ carried away with myself,” he tells me at one point.

“But thousands of small investors will see hundreds of millions of dollars of gain. It’s a righteous cause.”

Needless to say, the asset managers that sponsor closed-end funds

see things differently.

Those firms as well as industry body, the Investment Company Institute,

characterise the likes of Saba as profiteering at the expense of long-term investors. Funds that are forced to tender have to spread fixed

costs over a smaller group, the critics argue. Trading liquidity in the shares is reduced. Funds that have to switch to open-ended format

cannot run with leverage or stay fully invested.

Saba has cut holdings in funds immediately after completing successful

campaigns, the hedge fund’s detractors say, showing the firm has no interest in good governance beyond its own short-term gains.

And shareholders other than Saba in some of the campaigns have voted

in favour of the status quo. Franklin Templeton said in a February statement that less than 10% of the fund’s shareholders other

than Saba had supported the hedge fund and its nominees.

Improved structures aim to ameliorate some of the stated concerns

of activists. Newer closed-end funds that are being targeted by activists have fixed terms of 12 years, so investors are not locked in

for ever, their sponsors say.

Some fund operators even claim Saba’s actions could kill

the industry, denying investors the benefits of the closed-end structure altogether. “Opposing Saba… is critical to preserving

closed-end fund options for retail and institutional investors,” BlackRock blasted in a 2019 statement. “Saba’s tactics

continue to weaken, and even potentially endanger, the closed-end fund landscape.”

Policymakers too have sided with fund providers in some jurisdictions.

The state of Delaware last year enacted measures that make it harder for firms like Saba to gain control of closed-end funds, requiring

approval from two-thirds of shareholders for an acquirer of more than 10% of stock to exercise its full voting rights.

Weinstein’s response to these criticisms is that closed-end

funds that tender or switch to an open-ended structure have no reason to cease operating, and that investors will most likely benefit

as any discount to NAV narrows.

“The argument you are depriving investors of something finite

or scarce is flawed,” he says.

Closed-end fund activism is different from activist campaigns against

companies in which each target is distinct. At the extreme, operators of closed-end funds could create new funds with the exact same team

and assets as a liquidated entity if investors demanded it.

“We aren’t depriving investors of investment fund options

and, in any case, they’re swimming in [options] – between ETFs, mutual funds, closed-end funds and all the rest. That argument

just doesn’t work,” Weinstein says.

Big bets

Saba looks set, then, to keep picking fights. People that know him

say Weinstein is inclined to take big bets when he senses opportunity. Right now, closed-end fund discounts in some markets are at close

to historical extremes.

There are risks, of course. Weinstein’s own early investments

lost money. “In the middle of 2013, I diversified into [closed-end funds] and it only cost me. The discount grew,” he says.

In 2020, average discounts for all equity closed-end funds reached

13%, with the worst funds trading much wider. During the global financial crisis, the average size-weighted discount was 24%, again with

some funds far wider.

The reasons for those collapses, though, no longer exist, Weinstein

asserts. In 2008 closed-end funds relied on leverage from the now largely defunct auction rate securities market. That market failed dramatically,

forcing the funds to de-lever and sell at the worst possible time.

In 2020, the bond market “broke”. Even high yield ETFs

briefly traded at 25% discounts to NAV. But the Federal Reserve stepped in, buying assets including corporate bond ETFs. And closed-end

funds rapidly recovered.

The Fed may not intervene in a similar crisis in the future, of

course. But Weinstein thinks such big discounts – even without intervention – could not persist. Firms like his own would

seek to arbitrage them away.

As long as Saba is able to stay in its trades, then, bigger discounts

present a bigger buying opportunity, he argues. (Yes, Weinstein bought heavily in March 2020.)

In addition to the BlackRock campaign, where might Weinstein set

his sights next?

The UK is the obvious choice. Closed-end funds number more than

400, with nearly $300 billion in assets under management. Over a third are trading at a discount greater than 15%, according to Morningstar

Direct.

The largest closed-end fund in the world is based in the UK –

the £13 billion ($16.6 billion) Scottish Mortgage Investment Trust. In fact, that same fund announced in May that it had bought

back shares worth £283 million in the past year to narrow a discount to NAV that had widened from 0.5% to 19.6% in 12 months.

A number of UK funds also include a clause in their bylaws requiring

a periodic continuation vote, which gives activist investors an automatic option to challenge the board. Shareholders in the UK with more

than a 5% holding can request a general meeting within 28 days and table a motion to terminate the manager.

The opportunity is “incredibly compelling”, Weinstein

says.

Saba now has a book of over half a billion dollars of UK closed-end

funds at a discount of greater than 15%, Weinstein says, which is very close to their widest discounts during Covid.

Correction, June 21, 2023: An earlier version of this article

understated the size of BIGZ’s trapped discount and contained inaccurate information about Voya’s prior voting threshold.

This has now been corrected.

Correction, June 22, 2023: An earlier version of this article

incorrectly stated that BFZ has a majority vote standard.

BlackRock Clashes With Hedge-Fund

Giant Over Control of Funds

Boaz Weinstein’s Saba Capital has

been buying up shares in three closed-end funds

By Jack Pitcher

July 29, 2023 10:00 am ET

Saba

Capital founder Boaz Weinstein accuses BlackRock of not caring about its investors. PHOTO: JASON

ALDEN/BLOOMBERG NEWS

Hedge-fund manager Boaz Weinstein is locked in a fight with BlackRock BLK

1.39% increase; green up pointing triangle over control of several investment products it runs, a battle that could upend

part of the mutual-fund world.

Saba Capital Management, Weinstein’s $4.4 billion hedge

fund, has been buying up shares in three of BlackRock’s closed-end funds that are trading at a discount to their

underlying assets.

Aiming to elect outsiders to the funds’ boards and force

changes to close that gap, Saba sued BlackRock and other asset managers last month over shareholder voting rights.

Closed-end funds are a type of mutual fund that issue a limited

number of shares when they go to market. Unlike with open-end funds—the far larger variety with which most investors are familiar—the

issuer of a closed-end fund doesn’t issue or redeem new shares. Because of this, closed-end funds don’t have to worry about

redemptions forcing them to sell positions at inopportune times. The flip side is that the lack of liquidity can lead to the fund’s

shares trading for more or less than the value of the securities in the fund.

Saba uses an arbitrage strategy at closed-end funds, aiming to

buy the shares at a big discount and posture for changes that will push them closer to their underlying value. In the past, Saba has agitated

for governance changes including converting funds to open-end portfolios or selling the underlying assets and returning the money to shareholders.

BlackRock is aggressively defending its funds from Saba’s

attack.

“The truth is this is a hedge-fund manager who is using

its sheer size and assets to take control of closed-end funds for its own benefit at the expense of the retail investor,” said Stephen

Minar, managing director of closed-end fund products at BlackRock.

The hedge fund has so far failed to elect new directors at the

BlackRock funds. Two of the funds didn’t reach the quorum required to elect new directors at their annual meetings.

In his lawsuit, Weinstein claims the world’s largest

asset manager is entrenching existing trustees and depriving its closed-end fund shareholders of their voting rights.

The suit, filed in New York federal court, targets 16 closed-end

funds run by BlackRock, Franklin Resources, Tortoise Capital Advisors, Adams Funds and FS Investments. It seeks to invalidate

what’s called a control-share provision, a law in some states that allows companies to cap the voting power of a single new shareholder

or associated shareholders.

The BlackRock funds in question are the ESG Capital Allocation

Term Trust, the Innovation and Growth Term Trust, and the California Municipal Income Trust. All three currently trade at discounts of

more than 10% to their asset value.

“This isn’t an attack on all closed-end funds—these

are funds that are at the bottom of the barrel in terms of discount,” said Weinstein, who is Saba’s founder and chief investment

officer. “These are the ones that are failing to offer their investors a chance to get close to net asset value.”

If courts rule in Saba’s favor and strike down control-share

provisions, asset managers would lose one of their primary defenses against proxy attacks.

SHARE

YOUR THOUGHTS

Who do you think has the

upper hand in the Saba Capital vs. BlackRock fight? Join the conversation below.

“If those cases come out the wrong way, I think there’s

real concern about the closed-end fund as a viable vehicle going forward,” said Kenneth Fang, associate general counsel at the Investment

Company Institute, an association of regulated funds such as mutual funds and ETFs.

Fang added that it can take years for new closed-end funds to

recoup their upfront costs for launching a fund, and new sponsors will be reluctant to launch funds if there is a high risk of losing

control to activists.

U.S. closed-end funds held $252 billion in assets at the end

of 2022 compared with $28.6 trillion in open-end funds, according to the Investment Company Institute.

BlackRock, which operates more than 50 closed-end funds, uses

several strategies to deter proxy attacks, in addition to taking advantage of control-share provisions. It employs

staggered board terms, ensuring a board can’t be overhauled

at a single annual meeting. In contested board elections at some funds, the challenger must win votes representing 50% of all shares,

rather than 50% of all votes cast—a difficult standard to meet because it is common for less than half of all shares to vote.

“We’ve been in dozens of campaigns where it hasn’t

come to this,” said Weinstein. “If I made a miscalculation, it is that I estimated BlackRock would actually give a damn about

their investors and not just about greed.”

Saba has won similar lawsuits against asset managers Nuveen and

Eaton Vance in recent years. It has also previously sued BlackRock over other board-election procedures at closed-end funds,

with some success.

In June, First Trust Advisors dropped control-share provisions

at 13 of its closed-end funds. BlackRock says different states have different control-share laws, so Saba’s past cases aren’t

directly applicable to its funds.

Weinstein has been vocal in his criticism of the governance

at BlackRock’s closed-end funds. He claims that five directors at the funds he’s targeting sit on the boards of at least 70

different funds. He names R. Glenn Hubbard, the dean emeritus of Columbia Business School, as an example. Hubbard is on the boards

of at least 70 BlackRock funds, in addition to serving as chairman of the board at MetLife and teaching at Columbia, Weinstein

says. Hubbard declined to comment.

Weinstein also points to what he calls the hypocrisy of BlackRock’s

proxy voting guidelines, which deem directors at the companies in which it invests to be overcommitted if they serve on more than four

public company boards.

“You really have to differentiate between an operating

company and an investment company like a closed-end fund,” said BlackRock’s Minar. “I think there’s actually significant

benefits of having directors serve on multiple boards in a fund complex—funds that are managed by the same investment adviser.”

Saba scored a win earlier this month when proxy advisory firm

Institutional Shareholder Services recommended investors vote for some of its shareholder nominees and withhold votes for all incumbent

directors at BlackRock’s ESG and innovation funds. ISS specifically recommended the removal of Hubbard at the muni fund.

Rajeev Das, portfolio manager and principal at Bulldog Investors,

an activist fund that specializes in closed-end fund arbitrage, said the arbitrage strategy is in its prime, given the number of funds

trading at steep discounts.

“It’s really a good time to be buying closed-end

funds, and discounts are wide across all asset classes,” said Das. “You’ve also got activist investors out there buying

these, and I think it is a good recipe for success.”

Write to Jack Pitcher at jack.pitcher@wsj.com

Corrections & Amplifications

Saba Capital currently manages $4.4 billion. An earlier version of this article incorrectly called it a $4.7 billion fund. Separately,

hedge-fund manager Boaz Weinstein’s last name was incorrectly spelled as Weinsten in one instance in an earlier version of this

article. (Corrected on July 30)

Appeared in the July 31, 2023, print edition

as 'BlackRock, Hedge Fund Fight Over Control of Investments'.

Hedge Fund Titan

Boaz Weinstein Gears Up For a $240B Crusade

• Saba

pushing back against ‘grotesque behavior,’ Weinstein says

• Fights

are over how to boost share prices in closed-end funds

Boaz WeinsteinPhotographer: Jeenah Moon/Bloomberg

Yiqin Shen and Vildana Hajric | Dec 18, 2023

(Bloomberg) -- In an oft-overlooked corner of the finance industry,

Boaz Weinstein is waging perhaps his most ambitious battle yet.

Fresh off two legal victories over fund giants BlackRock Inc. and

Nuveen, Weinstein — a veteran credit derivatives trader who played a key role in taking down the London Whale —

has his sights on upending the $240 billion closed-end fund industry.

At stake is upwards of $17 billion in total potential gains for

investors in the funds.

To hear Weinstein tell it, his activism in the closed-end fund industry,

which spans the better part of a decade, is rooted in its mismanagement. Too often, fund managers are more interested in collecting fees

than maximizing returns for shareholders, who mainly consist of retirees and others seeking steady income. If he succeeds, they’ll

benefit too.

“We’re pushing back against grotesque behavior from

some in the asset-management industry,” Weinstein, who runs Saba Capital Management, said in an interview. “We’re pushing

back on the ones where the manager is acting in a problematic way that without us, there’s no hope for them because the retail investor

cannot defend themselves.”

If it sounds something like a crusade for the greater good, his

antagonists are having none of it. Many in the closed-end fund industry are fighting him in court and call firms like his “pirates”

looking for nothing more than short-term profits at the expense of more patient investors.

What’s not in dispute is just how much money Weinstein has

put on the line in recent months. Nearly 70% of Saba’s $5.6 billion in equity assets were in closed-end fund positions as of December,

according to data compiled by Bloomberg, more than twice as much in dollar terms as the same period last year.

Weinstein’s fights center around funds that buy income-producing

assets, like junk bonds, municipal debt, or dividend-paying stocks, that have been clobbered by the Federal Reserve’s rate-hike

campaign. With bond prices plunging across markets, investors have looked to bail out of closed-end funds.

That exodus has pushed down the stock prices for the publicly listed

funds to bargain levels, often below the value of the assets they hold, known as the net asset value or NAV. The scale of the discounts

is breathtaking: nearly half of the 243 closed-end bond funds in the US trade at a discount of at least 10%, while in March 2022 less

than a tenth did, according to John Cole Scott at Closed-End Fund Advisors . Bond funds account for about 60% of the closed-end

fund universe, he said.

If activists like Weinstein could erase the discount in every US

closed-end fund trading for less than net asset value, investors could earn about $17 billion, according to David Cohne, a mutual fund

analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence, who looked at data through Nov. 30.

The discounts arise from the unusual way that the funds are put

together. Closed-end funds are designed to be able to buy and hold assets long term. They sell shares in an initial offering, and then

invest the proceeds. When one of the original shareholders wants to exit the fund, they must sell to another investor, but the closed-end

fund keeps investing the money it originally raised. When too many investors are looking to exit, the shares can trade below the value

of the fund’s assets.

That’s different from open-end funds, where an investor who

wants to exit redeems their shares with the money manager and gets paid in cash. The fund might raise that money through selling off some

of the assets in the underlying portfolio. Weinstein often presses money managers to turn their funds into open-ended funds, exchange-traded

funds, or other vehicles where investors can easily cash out and get the full market value of their investment.

“In closed-end fund activism, the medicine of open-ending

into a mutual fund or ETF or a tender will collapse the discount every time — and all investors benefit,” Weinstein told Bloomberg.

That pressure might come through electing new directors to the boards that

oversee funds. If the closed-end fund resists the pressure, by for example making it harder for Saba to vote in new directors, the hedge

fund is willing to sue. A US court in New York this month ruled that 11 funds, some managed by BlackRock, had illegally stripped Saba

of votes when they implemented rules limiting how many shares could be used for voting.

An appeals court at the start of December ruled that Nuveen had

also illegally blocked Saba’s efforts. A spokesperson for Nuveen said the firm and the trustees for the funds were disappointed

with the ruling, saying in a statement that “Nuveen believes that this ruling will harm the interests of long-term shareholders

across the broader closed-end fund industry.”

Switching a fund to an open-ended structure often translates to

money managers having to sell assets they had expected to hold long-term. The fund’s assets will often shrink further, as will its

fee income. Investors who remain can be hurt, according to Kenneth Fang, associate general counsel at the Investment Company Institute,

a trade group. He called activist hedge funds “pirates.”

“They are coming in and seizing upon the discounts, looking

for liquidity events to get out pretty quickly so that obviously they can earn short-term profits,” Fang said. “But when they

do that, they leave a whole bunch of remaining investors in a worse situation — they are left with a fund with less assets and have

lost the economies of scale that they had with the larger fund. And, thus, expenses creep up.”

A spokesperson for BlackRock said, “The real victims here

are hardworking Americans seeking a secure retirement, not a billion-dollar hedge fund.”

BlackRock’s closed-end funds and their boards of trustees

have taken steps to improve shareholder value, including increasing distributions for shareholders and launching funds that offer investors

100% liquidity at net asset value on a future date, the spokesperson said.

Investors should be able to pull money out of funds without having

to sell at below net asset value, and shift into other assets, Weinstein said. Closing fund discounts through an activist campaign can

take years, and often isn’t just a quick way to get easy returns. And fund managers that disagree are mainly looking to keep up

their asset levels so their fee income won’t fall, he said. Investors benefit by getting more ready access to their funds.

“Saba received countless thank-yous from the mom-and-pop investors

who spent years in funds stuck at double-digit discounts to NAV,” Weinstein said.

Weinstein's

Saba Sues BlackRock Fund Over 'Entrenchment Bylaw'

By Yiqin Shen

_____________________________________________________________________

Saba

Capital Management filed a lawsuit against the BlackRock ESG Capital Allocation Term Trust (ticker ECAT), a closed-end fund, for adopting

an "entrenchment bylaw" that it says "deprives shareholders of their right to elect directors annually."

| • | READ MORE:

Boaz Weinstein Battles BlackRock,

Nuveen in $240 Billion Crusade |

| • | "BlackRock

holds itself up as a leader in corporate governance despite the fact that many of its funds,

including the CEFs, entrench compromised

trustees, hinder

shareholders' rights

and put up roadblocks when attempts are made to narrow persistent discounts to net asset value," Saba founder Boaz Weinstein says

in a press release |

| • | Saba also announced its nomination

of candidates for election to the boards of trustees of 10 BlackRock closed-end funds, including the BlackRock California Municipal Income

Trust (BFZ) and BlackRock Capital Allocation Term Trust (BCAT) |

| • | The lawsuit

comes as Saba ramps up pressure campaigns against some of the biggest managers in the closed-end fund space.

The firm tends to focus on funds that trade

at steep discounts to the value of their assets,

pushing money managers to take steps like buying

back shares and liquidating funds to boost returns for investors |

| • | "This

is another attempt from Saba's predictable playbook to over-burden the fund and its board while Saba continues to accumulate shares in

order to control votes and force actions that leave long-term shareholders worse off," a BlackRock spokesperson said via email |

(Updates

with BlackRock comment in fifth bullet)

To

contact the reporter on this story:

Yiqin

Shen in New York at yshen358@bloomberg.net

To

contact the editors responsible for this story:

Eric J.

Weiner at eweiner12@bloomberg.net

Boris

Korby

Exhibit

3

Exhibit 4

Boaz

Weinstein – CNBC Squawk Box Interview Transcript

May 14, 2024

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MET90PmKlfI

Andrew Ross Sorkin:

We're right here now at Saba Capital Management's office in Midtown

Manhattan. And joining me in a rare and exclusive interview is Boaz Weinstein who's the founder and CIO of Saba Capital Management, made

famous perhaps for the London Whale, but now bringing a new activist campaign to BlackRock, which is a fascinating new development in

terms of going after their closed-end funds. You've made a strategy of going after closed-end funds now for several years.

A lot of folks may not understand what a closed-end fund is. So

before we even maybe get into the conversation about what is it that you're trying to do and going after the governance of BlackRock,

a firm that's made its name in large part on the back of governance and governance issues, what are you trying to do with BlackRock?

Boaz Weinstein:

Right. So closed-end funds are, they've been around for more than

a century. A lot of the viewers will recognize the Grayscale Bitcoin Trust is a very famous closed-end fund. It was at a discount for

years, a very deep discount, and when it converted into an ETF, the discount disappeared. Investors made something like 80 or 90% from

that discount going away. On the New York-London stock exchanges, there are over 700 of these closed-end funds. There are portfolios of

assets managed by venerable managers like BlackRock. And sometimes unlike ETFs, unlike mutual funds, they trade at deep discounts to their

objective value. And that discount can be corrected with the press of a button, and that's what we're here to do.

Andrew Ross Sorkin:

So let's go into why do closed-end funds as a matter of practice,

seem to run at a discount? They trade at a discount almost across the board.

Boaz Weinstein:

Right. So there are periods when they're at discounts. In fact,

there are many today that are at premium. But why do the BlackRock ones trade at discounts and why in general do they? It's because there

isn't really a sophisticated investor base who wants to own these products. They have high fees, and so at fair value, you could say,

"I'd rather be in an ETF that does the exact same thing. So, I'm not going to buy it unless it's at a discount." And until it

gets to double digit discounts, there aren't really investors like myself that will take up the effort of buying them.

Andrew Ross Sorkin:

Okay. But what is it exactly, that's your problem with BlackRock

specifically? And you have been at war, dare I say, with BlackRock now for several years, and you've gone to court with them too.

Boaz Weinstein:

Successfully, yes. We won in federal court in December. One of

the things we were at war with was that they were violating the Investment Company Act, the Sacred 1940 Act, that they prevented us

from voting all of our shares, even though the Company Act says every share gets to vote. And in federal court on summary judgment,

the judge said, "Saba wins. BlackRock cannot do that anymore." So that was one thing.

Our issue is not really about performance, though some of

these funds have performed terribly, to use a technical word. In the last three years, nine of the 10 funds that we're even talking about

have lost money for investors. Negative total return, nine of these funds. Performance is one thing, but the performance is exacerbated

by this discount because a dollar of stuff, whether it's IBM or Bitcoin or municipal bonds that BlackRock manages despite their $10 trillion

in their brand, a dollar of stuff is trading freely for 85 cents, 83 cents, 86 cents on the dollar.

And our problem is that having become the largest shareholder in

many of these funds, they're actually blocking us from speaking to shareholders. And ISS last year called them out and withheld on their

nominees for what ISS termed abusive corporate governance practice.

Andrew Ross Sorkin:

Let me ask you this though. Some critics would say, "Look,

the closed-end fund is sold as a closed-end fund," meaning they raise money in the beginning and the plan is for you to hold it for

12 years and at the end of the 12 years, you get your money back and hopefully more than that. And yes, it may trade at a discount in

between, but that's what it is and that you dear sir, are hijacking the process by saying, "Actually no, the product shouldn't be

this. It should be something else."

Boaz Weinstein:

Right. So first, most of the funds that they have, they have over

70 are forever funds. They're not 12-year funds. It's only recently that they've kind of tried to split the difference and make it have

a term to it. So this idea that a fund that started as one thing needs to be that thing nine years later.

First of all, we don't have a plan to convert it from a closed-end

fund into an open-ended fund necessarily. In the last decade, we've done this about 60 times - most of the time to get rid of this overhang

of too many people wanting to sell it at a discount. The manager goes and buys back those shares. They tender for shares at net asset

value and investors who want to come out, come out. The ones who want to stay, can stay in their closed-end fund for a hundred years if

they want, and often that does get rid of the discount. There was a Neuberger Berman fund that did that and they're trading today NHS

at a premium after doing a tender.

Andrew Ross Sorkin:

How much money do you think is on the table here if you're successful

for shareholders?

Boaz Weinstein:

That's what's wild about this because traditionally these were small

funds, but BlackRock does everything in supersize. These 10 funds that we've nominated people to the board of — If BlackRock pressed

a button like we've done before six dozen times and allowed investors to get out just at fair value — They don't have to be right

about where AMC is going to trade tomorrow. They don't have to be right about the Fed. If it just traded at net asset value, the number

is staggering, Andrew. It's $1.4 billion.

Andrew Ross Sorkin:

I want to read you a statement from BlackRock. Obviously, they are

not happy about your efforts to try to upend these funds. This is what BlackRock has to say about all this and maybe you can react to

it. They say that BlackRock has a 36-year history of managing closed-end funds for millions of American retirees, I should say, who they

say depend on them for income. Saba is not a champion for the retail investor, but an activist hedge fund they say looking to arbitrage

funds in order to capture quick profits.

This attack is not about governance performance or discounts, which

narrow over time. It's about executing Saba's well-known playbook, they say buying controlling positions, enforcing short-term changes

that harm retail investors to benefit Saba and its hedge fund investors.

Boaz Weinstein:

First of all, there isn't one word that they said that's at all

accurate. The retail investor benefits exactly the same way as Saba. We haven't achieved some return and we leave everyone else high and

dry. The retail investors are some of the least sophisticated investors in the world. The president of BlackRock, I sat in his office,

Rob Kapito's office seven years ago and he said, "Kid..." And I was 43 at the time. He said, "Kid, these products are sold,

not bought," meaning no one calls their broker and says, "Get me the latest BlackRock fund."

It is pushed on them by their financial advisor. It has slightly

higher fees than it should. It has this super long, maybe perpetual term, which BlackRock loves because they get to manage the money forever.

And so the idea that the retail investors relying on funds where ironically. We're here in a bull market, Andrew. I don't know if you've

looked at the stock market. These nine funds are down over the last three years. Total return is down. Some of them as much as 54%. And

so this idea that the shareholder, which all we want to do is vote — We don't want to decide the matter. We just want to be able

to vote. The idea that the shareholder needs these funds when there's an infinite number of mutual funds and ETFs with very low fees that

BlackRock manages, by the way, the idea that that is not something that is worthwhile for them to take right now, a giant recouping of

a loss to go from 85 cents to a hundred cents.

We would make investors, and they have not disputed this math and

I've called them out to dispute the math, $1.4 billion dollars would be made if these funds traded as well as their ETFs.

Andrew Ross Sorkin:

You don't think that the investors in these funds actually want

these funds to begin with? You believe that they've been effectively foisted on these investors?

Boaz Weinstein:

Look, there's a mix. First of all, there's sophisticated retail

investors that buy the funds that we buy, whether it's copying us or on their own. There are investors that bought it at IPO and it's

been passed on to them from their descendants. A lot of these investors… Who buys high fee closed-end funds at IPO? The least sophisticated

investors. And all we want is to have a fair vote.

Now, the thing that will shock is that the vote that BlackRock will

take next month is to count people who don't vote as if they were BlackRock votes. And that's the thing that they're doing in this election

that makes my head explode. But they would never dare do that for BLK stock. They're treating their shareholders in their stock versus

their shareholders in their closed-end fund stock, like second class citizens compared to BLK.

Andrew Ross Sorkin:

Okay. The critics say the following. And so I'll ask you. You have

done this before with several other funds. Either publicly now, GIM and Saba among them. Those trade at a discount too even today, and

you're in control of them.

Boaz Weinstein:

Right.

Andrew Ross Sorkin:

So what do you say about that? If yours are not necessarily performing

that much better than theirs?

Boaz Weinstein:

Right. So firstly, the critics are a lobbying group called ICI that

works for the managers. Second, our fund, which was when we took over three years ago, the ticker is BRW. People can go to the website

and see the letter we wrote. In 2022 the year after we took it over, we were the number one performing income closed-end fund out of 257

funds. So they can say what they want. Now to the question of the discount. Okay? Good question, right? That's a hardball question for

me.

In GIM and in PPR, which became Saba funds, BRW and SABA, we offered

investors first a 70% tender, which not even 70% of the shares tendered. We got management to do that. We took it over and then we offered

a 30-tender and then a 15-tender. We offered more than a hundred percent of the shares to be bought back if anyone wanted to.

Andrew Ross Sorkin:

Any investors could get out if they wanted?

Boaz Weinstein:

At asset value is the point or right at asset value. And the investors,

some of them did and some of them said, "We want to be with you. We want what you are changing this fund into." And that fund,

I'm proud to say, has actually outperformed all of these BlackRock funds by somewhere between 19 and 64%. So let them take shots at my

fund. But yes, they are at small discounts. That's true.

Andrew Ross Sorkin:

Maybe also hardball, have you lowered the fees on those funds since

they became yours?

Boaz Weinstein:

So one of them is already a very low fee fund. It's only 75 basis

points. What we have done is set in place governance. We changed the governance to be best-in-class. The elections are held annually,

the votes are counted on how many votes you get, not the non-voters counting against you. And more than that, the managers of closed-end

funds. This is something that's probably not well understood. They charge fees on what's called managed assets. So if they lever up, you

pay more fees.

Now, when you invest in my hedge fund, if I want to lever up or

lever down, it's the same management fee. So for my funds, I have not been running it at full leverage. I've been waiting for there to

be an opportunity. We lever up, we don't like it, we lever down and we're not maximizing fees. These other BlackRock funds are always

fully levered.

Andrew Ross Sorkin:

Okay. I'm going to try one more on you.

Boaz Weinstein:

Please.

Andrew Ross Sorkin:

This is the Ohio Sentinel Tribune op-ed in January. I'm sure you've

read it. It says three years ago a hedge fund firm took over a closed-end fund. They changed the investment strategy from a reliable ‘senior

loan fund’ to a fund holding risky assets, including crypto. Worse yet, they liquidated their shares, leaving unwitting retirees

holding the bag. The same playbook seems underway on another closed-end fund now. They are referring to this, the BlackStone story. This

flies in the face of the basic principles of the Investment Company Act, the current law that is intended to separate hedge fund billionaires

and fund insiders from the rest of us and stops them from eating our investments lunch.

Boaz Weinstein:

Right. So again, not a holder of the fund, but a pro-advocacy person

putting that story in. So that fund that got into crypto, that's the one I was talking about. First, we offered people an exit near net

asset value. And so we gave them the gain that we're asking BlackRock to give to make this 1.4 billion. Then we asked for approval to

change the mandate from a reliable loan fund, which was invested in single beat junk, junk loans, junk-graded loans, and we got approval

from ISS. 99% of the shareholders approved those words that you just said. We then invested and we were the number one fund in 2022. So

that's what I have to say about that.

Andrew Ross Sorkin:

You talked about talking to Rob Kapito of BlackRock a long time

ago, seven years ago. Have you ever called up Larry Fink about any of this? Did he take your call?

Boaz Weinstein:

We don't know each other, and I'm perfectly happy to do so. If someone

from BlackRock wants to send me his number, I'd be glad to because if only he did it, it actually would be beautiful for his brand. His

employees own these funds. They're rooting for the discount to go away. Who would not want this short-term gain? It's not short-term.

We've been in these funds for years. What's the long-term pain that you might have a smaller fund that BlackRock's managing that you might

have to go to one of a million other choices?

A billion-four hangs in the balance. And as you know, Andrew, making

money, unless you buy GameStop today is really hard. A billion-four can be made, literally, if it became one of their ETFs or mutual funds

or if they did a tender.

Andrew Ross Sorkin:

And you've now started a website called heyblackrock trying to get

their attention. Trying to get their attention or maybe trying to get the shareholders' attention.

Boaz Weinstein:

Really the shareholders' attention. Heyblackrock.com was set

up because when you fill up your account at Schwab or Bank of America, you get asked, "Do you want to be contacted in these

sorts of matters?" And BlackRock is not giving us the names of the people who asked to be contacted, which is also unusual. So

we have to get the word out, whether it's talking to you on Twitter or heyblackrock.com where we are going to hold a webinar on the

20th, take investor questions and go through the plan.

Andrew Ross Sorkin:

While we have you here, you mentioned GameStop. We've been following

that story this morning and you play in the markets every single day. I see there's a whole trading floor that way. People can't see it

on camera. What do you make of what is happening right now in the markets and specifically, actually, when you look at a GameStop. I mean

you are an investor. Is this investing?

Boaz Weinstein:

It's bewildering because we want to make 10%, we want to make 15%.

You see something that's up a hundred percent, you don't know why. It feels great because it's up, not down, for those who have it. But

it certainly in some ways you could say makes a mockery of the challenge of investing because it can't be justified on anything other

than pure speculation. Why today? Why not a million dollars a share? And so I look at it and I don't understand it and I don't want any

part of it.

Andrew Ross Sorkin:

Is this different? We were talking recently on our air with Gary

Gensler and I mentioned the Trump SPAC for example, which also seems to trade this way. You were involved in that SPAC early and then

got out.

Boaz Weinstein:

So I ended up being one of the five largest holders of the Donald

Trump Truth social trust because I didn't buy it knowing that. I bought it when it was a SPAC and then they decided to merge with that

company. So at that point, the SPACs which we actually had in the funds that you read that Ohio Sentinel piece about were at a very attractive

discount. They were T-bills in a box. Then they decided to buy this Donald Trump truth social, and it went to the moon.

And I again, didn't want any part of it because it's a little bit

of greater fool. If it's at 15, it can go to 16. If it's at 50, you feel badly that you sold it at 15, but it was at nine a minute ago.

And so, I like when you have this supernormal gain in something to take chips off the table if I'm lucky enough to even be there.

Andrew Ross Sorkin:

From a governance perspective and market integrity perspective,

given that that's part of what you're talking about here in the context of BlackRock, what do you think should happen? I mean, we had

Jay Clayton on earlier, former head of the SEC, and we're talking about market manipulation and the like. Do you think there's something

that should happen to the memeification of the markets?

Boaz Weinstein:

I think it's very hard to put in place rules to say this gain is

too much. The news doesn't justify that. I think it does feel like greater fool theory, but I'm not sure who's doing something wrong to

someone else. Obviously if there are people pumping it up, but I don't know anything about that, so I really don't have a view about it.

Andrew Ross Sorkin:

Separately, just, you're someone who spends a lot of time both looking

at arbitrage opportunities, but also looking at the broader markets and where things are, and I think looking also for cracks in it. Where

are we in this market? Do you see cracks? Should we be worried? Are you bullish? Are you bearish?

Boaz Weinstein:

So, the market is foggy. We had six fed cuts priced in just a few

months ago. Now we have one. Maybe we're going to zero. The way things change is inflation. Has it been kicked? Are we going to have higher

for longer? I think that there's a very heightened amount of uncertainty, even just take the geopolitical skirmishes slash wars that we

have. And so when you put all that together higher for longer, which means higher interest rates, which may be great for the lender, but

for the borrower is terrible. We are going to, I think, have a credit crunch in the next couple of years if things don't change.

And even you take the 100 leading economists, they're pricing about

a 35% chance of recession, a hard landing. Yet the credit market, just look at corporate credit spreads are almost at the lows of all

time. And so I think that credit does not offer investors any kind of suitable margin of safety right now. Corporate credit that is.

Andrew Ross Sorkin:

So you just spend all of your cash in the equity world?

Boaz Weinstein:

Well, we own 6 billion SPACS. I should have said that at the time.

Sorry, not SPACs, closed-end funds.

Andrew Ross Sorkin:

Closed-end funds.

Boaz Weinstein:

We used to have 6 million SPACs, and then we're very involved in

protecting pension and endowment portfolios from a sell-off using credit derivatives, which is my domain expertise.

Andrew Ross Sorkin:

When you look at just even over the next 12 months, we talk about

this being an election year and the like. Does that change anything?

Boaz Weinstein:

It's huge. If Trump is elected, it's going to affect the relationship

between equity and fixed-income markets quite a bit because he seems to want the stock market to go up. The promising across-the-board

tax cuts, who's going to pay for that? So more debt, higher interest rates. And I would say Trump is likely to lead to more volatility,

all things equal than Biden. Although once the election... Maybe in both cases, there's going to be plenty of volatility and I'm quite

excited for it.

Andrew Ross Sorkin:

You're quite excited for it. Finally, just on the timing of this

whole BlackRock situation, what is the next step in it?

Boaz Weinstein:

Yeah. So we've sued them again, first successfully last year in

federal court for not letting us vote all our shares. This year, it's for not counting the votes properly, for basically saying anyone

who doesn't vote counts for BlackRock. That suit is going to get some resolution and then we'll see how the votes will end up being counted.

The voting will be done between now and depending on the funds, July 3rd is when it all is over.

Andrew Ross Sorkin:

Okay. Boaz Weinstein, thank you for joining us this morning and

having us right here this morning to talk about this. Thank you.

Boaz Weinstein:

Thank you.

Andrew Ross Sorkin:

Appreciate it. Becky, back to you.

Becky Quick:

Andrew, that was fascinating. Every aspect of it. One very quick

question. I don’t know if he can answer this. He was saying his fees on his fund are very low at 75 basis points. What are the fees

that they're talking about on some of these Blackstone funds — or BlackRock funds? I'm sorry.

Andrew Ross Sorkin:

You can't hear Becky, but one of the questions she was just asking,

and she was fascinated by the conversation, was on the fees and we're talking about the 75 basis points. What are the fees that Blackstone

has on its funds?

Boaz Weinstein:

So BlackRock funds, their fee-

Andrew Ross Sorkin:

I'm sorry, not Blackstone, BlackRock.

Boaz Weinstein:

Yeah.

Becky Quick:

That's my fault.

Boaz Weinstein:

So one of mine is 75, one is percent. Theirs are more like 1.1 at

range, but their ETFs are about half of that. So if someone went from a ESG, closed-end fund run by BlackRock to an ESG, open-ended fund

run by BlackRock, they would be getting a very similar portfolio, same level of care, and they would save about half the fees.

Andrew Ross Sorkin:

How important is it for you to ultimately control the funds versus

for them simply to shift and do what you want them to do?

Boaz Weinstein:

Shifting would be massive. In fact, of the 60 or so campaigns, we

only ended up running the funds twice. What we want is for shareholders, which we are the largest of, but not in any way the majority,

to make that $1.4 billion, which can be done at the press of a button. And they have not disputed that ETFs and mutual funds trade at

NAV, tenders at NAV, allow you to get out at NAV 1.4 billion to their shareholders and a lot of good brand image from having done so.

Andrew Ross Sorkin:

Boaz Weinstein. Thank you.

Exhibit

5

Fellow Stakeholder:

Thank you for your interest in our campaign

to hold BlackRock accountable for destroying billions in shareholder value at 10 of its CEFs.

Saba's Founder and CIO Boaz Weinstein joined

Andrew Ross Sorkin on CNBC earlier today to share his views on why BlackRock CEF shareholders deserve better. In case you missed it, you

can watch the full interview at the link below.

On May 20 at 11:00am EST, join us for

a live webinar where Boaz Weinstein will answer your questions and share his plan to improve the BlackRock CEFs.

We urge shareholders to elect all of our proposed

directors at the BlackRock CEFs' 2024 Annual Meetings in June. For more information on how to vote the GOLD Proxy Card for

each of our proposals, visit www.HeyBlackRock.com.

We appreciate your interest in our campaign

for change at the BlackRock CEFs.

Sincerely,

Saba Capital Management, L.P.

BlackRock NY Municipal I... (NYSE:BNY)

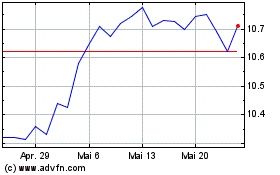

Historical Stock Chart

Von Apr 2024 bis Mai 2024

BlackRock NY Municipal I... (NYSE:BNY)

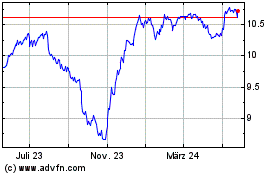

Historical Stock Chart

Von Mai 2023 bis Mai 2024