By Pamela Newkirk

When my book "Diversity, Inc.: The Failed Promise of a

Billion-Dollar Business" was published a year ago, I couldn't have

imagined how much events during the summer of 2020 could advance

our national conversation on race. Where before the killing of

George Floyd a large segment of white America believed that the

nation had largely overcome racial barriers -- indeed, many

insisted the nation was postrace -- there now is growing

recognition of the extent to which race continues to pervert our

national ideals. The kind of policing so graphically illustrated in

Mr. Floyd's open-air killing has pried open the eyes of many to

stark racial disparities that extend to health, housing, education

and employment.

Not only are African-Americans far more likely than whites to be

viewed as suspects, or contract and die of the coronavirus, they

have just one-tenth of the wealth of white families. And they --

along with nonwhite Hispanics -- are also disproportionately

underrepresented in every influential field, including law,

fashion, film, publishing, college and university faculties, and

corporate boards.

The question now is how to move forward to realize a more

racially just society. How can we as a nation capitalize on this

rare moment of racial reckoning, which comes in the wake of a

contentious election and amid uncertainty about our economy,

environment and public health?

In "Diversity, Inc." I question why, despite five decades of

deliberations, hand-wringing and billions devoted each year to

diversity initiatives, racial minorities remain disproportionately

and acutely underrepresented in most influential fields. And why is

the diversity business thriving -- fueled by the hiring of chief

diversity officers and consultants and the implementation of

antibias training and climate surveys -- while racial diversity is

not? History, after all, can steer us away from decades of costly

tried-and-failed practices.

In recent years, a number of extensive studies have shown that

not only has diversity training failed to realize diversity, but in

some instances can make matters worse. A 2016 study by sociology

professors Frank Dobbin of Harvard University and Alexandra Kalev

of Tel Aviv University found that mandatory antibias training not

only stoked a backlash, particularly among white men, but five

years after implementation, the number of Black female and Asian

male and female managers, on average, decreased.

Yet many institutions continue pouring millions of dollars into

a bloated and largely futile diversity apparatus, while bypassing

far more efficient and efficacious models. Habit and protection

from legal liability might help explain why. Research by University

of California, Berkeley, Prof. Lauren B. Edelman, for example,

found that in federal civil-rights cases, judges base company

compliance on the mere presence of diversity policies, programs or

officers, rather than on their efficacy.

To actually move the needle on diversity, institutions can begin

by redirecting their efforts away from programs designed to change

hearts and minds, and toward proactive interventions.

For starters, institutions need to expand their outreach beyond

well-worn pipelines that perpetuate exclusionary hiring, to

institutions and professional organizations of color that many of

them habitually overlook. Because of the segregated nature of our

society and the reality of homogenous professional workplaces, the

grapevine -- intentionally or not -- often sustains homogeneity.

Exclusion begets exclusion, and the cycle can only be broken by

discarding dated arguments about a pipeline problem and tapping

into unfamiliar networks. Only then will institutions discover the

legions of professionals of color, including many who graduate from

some of the nation's top schools. Companies can begin by forming

bridges with graduate schools and professional organizations of

color that could shore up diverse candidate pools.

Another often overlooked strategy is mentoring, which can do

more to ensure the success of current employees and future

prospective candidates of color than canned diversity programs have

been shown to do. However, in talks at a number of companies, I've

been struck by the unease many white professionals feel toward

their colleagues of color. This discomfort, born of segregated

neighborhoods and social spheres, along with prevailing stereotypes

that taint their judgment of Black and brown people, is perhaps

inevitable. But unless institutions build mentoring into the

development of employees -- including those of color -- diversity

is unlikely to flourish.

Large institutions also can adopt the kind of system of

assessment and accountability that was instituted at Coca-Cola Co.

following a landmark discrimination lawsuit settlement in 2000.

Steve Bucherati, who had been working in global marketing when he

was asked to oversee the company's diversity efforts, developed and

oversaw a system to assess and disrupt patterns of racial

disparities in pay, promotion and opportunity.

He began by assessing the status of candidate pools and employee

positions, pay, bonuses, promotions and work evaluations along

racial lines to detect and disrupt any patterns of bias. The system

allowed the company to address, in real time, any instances of

racial inequity before final decisions related to hiring,

promotions, salaries, bonuses and the like were made. Transparent

metrics, committed leadership and a system of accountability

enabled the company to significantly increase its diversity,

including in management, over a five-year period. Despite the

progress made after the settlement, Coca-Cola acknowledged more

recently that it still faces diversity challenges. Chief Executive

James Quincy told employees in a June town hall that while

African-Americans make up 19% of the company's U.S. workforce, they

hold only 7% of senior leadership positions. "We need to be more

effective in making progress," he said. The acknowledgment

underscores the need for ongoing vigilance.

Not even the best efforts will succeed without buy-in from the

board and CEO, and sufficient support of those entrusted to deploy

a diversity strategy. Tellingly, a 2019 Russell Reynolds survey of

Fortune 500 chief diversity officers showed that only 35% had

access to the company metrics that would even allow them to assess

the problems, and many said they didn't have the support or

resources needed to succeed. So while in the wake of Mr. Floyd's

killing many corporate CEOs have asserted that "Black Lives

Matter," they can best demonstrate their commitment by taking the

lead on one of the critical issues of our day.

Dr. Newkirk is a journalist, a professor at New York University

and an author of several books, including "Diversity, Inc.: The

Fight for Racial Equality in the Workplace." She can be reached at

reports@wsj.com.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

December 14, 2020 11:14 ET (16:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

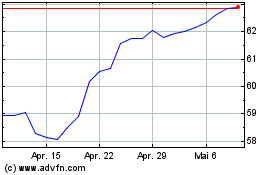

Coca Cola (NYSE:KO)

Historical Stock Chart

Von Mär 2024 bis Apr 2024

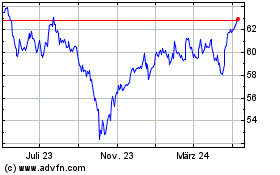

Coca Cola (NYSE:KO)

Historical Stock Chart

Von Apr 2023 bis Apr 2024