By Christopher Mims

If the partisans of America's elected leadership seem to agree

on almost nothing these days, Wednesday's Big Tech antitrust

hearing was stark evidence that they do share one common

target.

Despite what were sometimes cantankerous and politically charged

exchanges between Republican and Democratic members of the House

Judiciary Committee, perhaps the most interesting line of the

hearing came at the start, when Rep. David Cicilline (D., R.I.),

chairman of the Antitrust Subcommittee, recounted a comment he

attributed to Rep. Ken Buck (R., Colo.): "This is the most

bipartisan effort I've been involved with in 5 1/2 years in

Congress."

What followed was a bipartisan roast of the heads of Apple Inc.,

Amazon.com Inc., Google parent Alphabet Inc. and Facebook Inc. --

four of the five most valuable companies in America. It was a

pandemic-era spectacle of scrutiny that evoked past congressional

grilling of the captains of other industries near the peaks of

their powers, from tobacco and finance to energy and steel -- only

this time, with the CEOs in virtual attendance via videoconference

software.

A rare moment of united purpose from a body otherwise bitterly

at odds over so many other issues, the hearing showed that the

effort to regulate tech companies is becoming a big-tent issue, and

possibly a place for compromise between conservatives worried

largely about constraints on their speech, and liberals worried

primarily about constraints on competition.

Rep. Jerrold Nadler (D., N.Y.), chairman of the Judiciary

Committee, opened his comments with a broadside comparing large

tech companies to the railroad-owning robber barons of old. He said

that the four companies own the digital rails on which countless

other firms depend, and that his committee would follow "in this

proud tradition" of determining whether current antitrust law is up

to the task of addressing the presumed harms of these

companies.

Then the Judiciary Committee's ranking Republican, Rep. Jim

Jordan (R., Ohio), declared, "I'll just cut to the chase: Big

Tech's out to get conservatives."

The common thread was the threat of outsize market power, and it

wove its way through more than five hours of testimony even as the

questions swung between the pet causes of the members.

While none of the CEOs -- who included two of the world's

richest men, Amazon's Jeff Bezos and Facebook's Mark Zuckerberg --

seemed to break much of a sweat, they clearly weren't comfortable

either.

They parried a combination of specific, even wonkish questions

about instances of allegedly anticompetitive behavior -- some based

on internal documents that hadn't previously been made public --

and accusations of partisan bias in how they treat speech on their

platforms.

The CEOs disputed the claims, argued that their products are

helpful and well-liked, and occasionally promised to get more

information. They remained polite, even when frequently cut off by

interrogators trying to squeeze more questions into limited

time.

Mr. Zuckerberg was asked repeatedly about Facebook's 2012

acquisition of Instagram and the way its then-CEO perceived his

approach as a threat to either sell or be destroyed. Mr. Zuckerberg

pointed out that Facebook's acquisition and investment had led to

success for Instagram that wasn't guaranteed when the deal was

made.

Mr. Bezos was grilled about a Wall Street Journal article from

April describing Amazon's use of data from its platform to compete

against the independent sellers on the platform that it calls

partners. He said Amazon values those merchants and that Amazon is

still investigating the Journal's findings.

Alphabet's Sundar Pichai was probed on Google's dominance of the

online ad marketplace, and asked about a specific accusation that

Google had collaborated with the Chinese government in a way that

potentially constituted treason. He strongly denied that

accusation, and said he had cleared up the matter in a meeting with

the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

Apple's Tim Cook, who received the least attention of the group,

was questioned several times about its control of its own app store

and the impact on rival app developers and on consumers. He argued

that Apple has consistently applied its rules across its app store,

and has eliminated fees from some categories of apps and

services.

There were also suggestions of potential interference in the

2016 election, both on and by platforms, and both for and against

the election of President Trump, and questions about why the

platforms should have the power to remove a video claiming

hydroxychloroquine was a cure for Covid-19. (Short answer from Mr.

Zuckerberg and Mr. Pichai: They follow the guidelines of health

authorities and remove anything that could lead to imminent harm;

in June, the Food and Drug Administration revoked its emergency-use

approval of the drug.)

At times, it was as if separate hearings were occurring, with

representatives, more or less divided along party lines, behaving

like a boat full of oarsmen who can't decide in which direction to

row.

But they kept circling back to the idea that without checks on

the power of these companies, now collectively worth nearly $5

trillion, the tech giants could abuse it.

At one point, Rep. Matt Gaetz (R.-Fla.) closed a statement in

which he accused Google of being deceptive in saying that it

doesn't manually tune its search results ( a Journal investigation

has found that in some ways it does), by saying that the company

could suppress or favor speech, and interfere in a U.S. election,

through its "market dominance."

There is no clear playbook for how to proceed -- even many of

those who do believe that antitrust action is required against Big

Tech say that the current laws and traditional notions of consumer

harm aren't well-suited for companies whose popular products are

often inexpensive or even free.

But the hearing's consistent hostility offers a signal of common

purpose to the groups that are actively pursuing some sort of

antitrust action against one or more of these companies: the

Justice Department, the Federal Trade Commission, and an assortment

of state attorneys general.

And, if past is prologue, that type of unified anger could be a

prelude to action by Congress itself. In April 2009, after the

financial crisis, seven bank CEOs were hauled in front of Congress,

and in July 2010 it passed the Dodd-Frank Act, which mandated a

litany of changes to Wall Street business practices and created the

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

All of this takes place against a backdrop of a global pandemic

-- one that is only strengthening the power of Big Tech -- and a

presidential campaign. Here too, the unusual concordance between

members of both parties stands out.

One issue on which both Joe Biden, the presumptive Democratic

presidential nominee, and Mr. Trump agree is that something must be

done to rein in Big Tech. On Wednesday, Mr. Trump tweeted, "If

Congress doesn't bring fairness to Big Tech...I will do it myself

with Executive Orders." Mr. Biden has signaled similar aggressive

intentions, saying at the start of his presidential campaign, in

May 2019, that breaking up Big Tech companies like Facebook is

"something we should take a really hard look at."

If substantial action against some or all of these companies

finally happens, this hearing may mark an unlikely watershed -- a

moment of relative unity in an era of division that showed

America's elected leaders are ready to rein in Big Tech.

Write to Christopher Mims at christopher.mims@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

July 30, 2020 10:32 ET (14:32 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

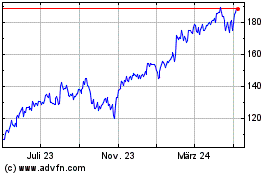

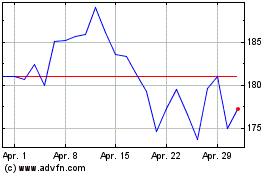

Amazon.com (NASDAQ:AMZN)

Historical Stock Chart

Von Mär 2024 bis Apr 2024

Amazon.com (NASDAQ:AMZN)

Historical Stock Chart

Von Apr 2023 bis Apr 2024