By Ben Eisen

Wells Fargo & Co. will pay $3 billion to settle

investigations by the Justice Department and the Securities and

Exchange Commission into its long-running fake accounts scandal,

closing the door on a major portion of the legal problems that for

years have beset one of the country's largest banks.

The deal resolves civil and criminal investigations. It includes

a so-called deferred prosecution agreement, in which the Justice

Department reserves the right to pursue criminal charges. The bank

has to satisfy the government's requirements, including its

continued cooperation with further investigations, over the next

three years.

Friday's settlement is a victory for Charles Scharf, an outsider

who took over as chief executive in October and was tasked with

fixing the crisis that has claimed two CEOs.

"The conduct at the core of today's settlements -- and the past

culture that gave rise to it -- are reprehensible and wholly

inconsistent with the values on which Wells Fargo was built," Mr.

Scharf said in a statement. "We are committing all necessary

resources to ensure that nothing like this happens again, while

also driving Wells Fargo forward."

The bank, though, still faces major regulatory problems. Most

notably, it is under sanction by the Federal Reserve, which has

taken the unusual step of capping the bank's growth. Settling with

the Justice Department and SEC could allow the bank to focus on

persuading the Fed to lift the cap.

As part of the settlement, Wells Fargo admitted that it

"unlawfully misused customers' sensitive personal information" and

harmed some customers' credit ratings, collecting millions of

dollars in fees and interest in the process.

The scandal severely damaged the bank's reputation with

customers and regulators alike, providing a case study of sorts on

how success in banking depends on customers trusting a firm enough

to leave their money there. It also has unsettled customers who

have long thought of retail banking as a service that takes

deposits and makes loans, not a sales-driven industry hawking as

many products as possible.

Regulators first fined Wells Fargo over the sales practices in

2016, alleging that executives created a pressure-cooker

environment in branches where low-level employees were so beset by

high sales goals that they opened up fake and unauthorized bank

accounts.

Afterward, regulators and lawmakers were outraged not just by

the allegations but by what they perceived as the bank's slow

response to them. What's more, with the bank under increasing

scrutiny, additional legal and regulatory problems sprang up across

other business units, including wealth management and

foreign-exchange trading. What was once a fast-growing lender whose

profits towered above those of rivals became a firm with declining

revenue that is leaning heavily on cost cuts.

The SEC portion of the settlement accused the bank of misleading

shareholders. According to the charges, Wells Fargo touted to

investors its ability to sell additional products to current

customers, a practice known as cross-selling, even though numbers

were inflated because of the fake accounts.

Aside from Friday's settlement, regulators and prosecutors could

still take action against former executives, according to people

familiar with the situation. Last month, the Office of the

Comptroller of the Currency charged eight former Wells Fargo

executives over the fake-account scandal, including a former

CEO.

Wells Fargo for years enjoyed a reputation as a folksy industry

darling that catered to Main Street customers. But that reputation

was left in tatters after the sales scandal became public.

"Wells Fargo traded its hard-earned reputation for short-term

profits, and harmed untold numbers of customers along the way,"

Nick Hanna, U.S. Attorney in Los Angeles, said Friday.

Prosecutors said the practices date to 1998, when Wells Fargo

began to rely more heavily on sales growth. It pressured employees

to cross-sell additional products to current customers.

The heightened pressure pushed many employees to open checking

and savings accounts without customer knowledge and make up

identification numbers to activate unauthorized debit cards.

Employees, afraid they would be fired otherwise, sometimes

forged customer signatures to open accounts or altered customers'

contact information to prevent them from learning about

unauthorized accounts, the government said. Sometimes they

persuaded friends and family members to open accounts they didn't

want or need.

Regulators and prosecutors said top managers knew of these

issues years ago. In 2004, an internal investigator called it a

"growing plague." In 2005, a corporate investigations manager

described the problem as "spiraling out of control." Employees

continued to raise concerns internally, the government said.

It also said certain executives "impeded" the OCC from

scrutinizing the sales practices.

After the scandal erupted in 2016, the bank's top executives

faced heavy criticism for holding lower-level employees

responsible. Wells Fargo fired thousands of branch employees, but

regulators, lawmakers and even the bank's own board questioned

whether the junior staffers were the ones to blame.

A board investigation found that the bank's decentralized

structure allowed top executives to avoid addressing these issues

as they got bigger.

Without referring to her by name, the Justice Department heavily

criticized Carrie Tolstedt, the former head of the consumer bank.

By 2012, regional executives "were regularly raising objections" to

Ms. Tolstedt about "unlawful and unethical sales practices."

Ms. Tolstedt is one of the former executives the OCC charged

last month. Her lawyer said Friday she "acted appropriately and in

good faith at all times, and the effort to scapegoat her is both

unfair and unfounded."

The House Financial Services Committee said Friday it is holding

three hearings about Wells Fargo in March. Mr. Scharf will testify

at one of them, his first appearance before the committee since he

took over as CEO. Members of the board will testify at another, a

spokeswoman for the bank said.

--Rachel Louise Ensign, Aruna Viswanatha and Dave Michaels

contributed to this article.

Write to Ben Eisen at ben.eisen@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

February 21, 2020 19:35 ET (00:35 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

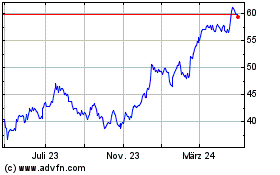

Wells Fargo (NYSE:WFC)

Historical Stock Chart

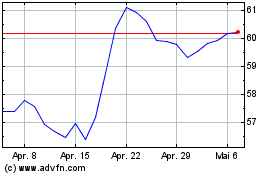

Von Mär 2024 bis Apr 2024

Wells Fargo (NYSE:WFC)

Historical Stock Chart

Von Apr 2023 bis Apr 2024