By Erin Ailworth | Photographs by Rachel Bujalski for The Wall Street Journal

PARADISE, Calif. -- Public schools Supt. Michelle John greeted a

gym full of teachers for a kickoff breakfast a day before the start

of the 2019-2020 school year. She spoke of loss, perseverance and

duty.

She expected about a third of the students from last year. Many

would be ferried into Paradise by families living outside of town.

"It's been, of course, the toughest summer of my life and we just

have to keep going," Ms. John said, her voice wavering. "We have

kids coming."

The first day of school gave residents a chance to take stock of

the prospects for Paradise, a town in the Sierra Nevada foothills

of Northern California threatened with extinction a year ago.

A PG&E Corp. transmission line sparked the 153,000-acre Camp

Fire, a galloping inferno that killed 85 people and in a matter of

hours on Nov. 8, 2018, burned 95% of the town. Many residents are

furious at the utility giant for its role in the fire that all but

destroyed Paradise.

The damage was so vast -- and the trauma to residents so

universal -- that Paradise may never again be what it once was.

Some predict a decadelong recovery for the town. Others fear its

demise.

"You've lost not only the homes, with it you've lost your tax

base and you've lost your economics," said Craig Fugate, a former

administrator of the Federal Emergency Management Agency. "Very

rarely can communities come back from that quickly, if ever."

Crews are clearing the last of the burned houses, dead trees,

scorched car frames, ash and debris. For months, heavy duty trucks

rumbled through neighborhoods, hauling away the ruins.

"Every truck I see is somebody's home," said Valerie Murufas, a

57-year-old Paradise native whose relatives lost nine houses. She

saved a few fragments of wedding china before her own lot was

scraped clean in July.

No more than about 3,000 of 26,000 Paradise residents have

returned. So far, nine houses have been rebuilt of the roughly

13,000 destroyed. One of the district's nine public schools was

untouched; four reopened this fall.

Much of what still stands in Paradise looks frozen in time: Gas

station signs advertise year-old prices. In one closed school,

classroom white boards still have Nov. 8, 2018, scrawled on

them.

The future of Paradise rests on whether enough residents decide

to return from the communities where they landed after the

fire.

"Once you put down roots somewhere else, once the kids are in

school somewhere else, once you have a job somewhere else, are you

really going to move back?" said Mr. Fugate, who led FEMA in the

Obama administration.

Nearly a year after the fire, Paradise hasn't fully restored

some of the basic elements that make up an American community:

jobs, schools, businesses, public services and clean water.

Signs at public drinking fountains warn away users because of

benzene contamination in the town's water supply from burned

plastics, soot and ash.

The Paradise Police Department lost about half of its officers

and is having trouble enlisting new personnel. "We're scrambling,"

Police Chief Eric Reinbold said. Two recruits are working their way

through the police academy.

The town of about 18 square miles has two grocery stores, five

restaurants and three gas stations that have reopened.

Adventist Health's 100-bed Feather River hospital remains

closed, leaving the school district the largest employer in

Paradise.

Those who have fought for the resurrection of Paradise include

Mr. Reinbold; a county social worker; the owner of a Thai

restaurant; the head of the local fire safety council; and Ms.

John, the school superintendent.

Four days after the fire, the air was still smoky when Ms. John

made her way to the charred entrance of Paradise Elementary. "This

was my office many years ago when I was principal," she said,

standing amid the wreckage.

A piece of a student's worksheet, blackened and singed, lay

among the ash.

Ms. John, wearing a gray Paradise High Bobcats sweatshirt,

didn't know of the obstacles ahead, both personal and professional.

She spoke of how all the students were safely evacuated. "We got

the kids out," she said.

She also talked about the job ahead, of getting the children of

Paradise back to class. Tears slid down her cheeks.

"We'll still be the Bobcats," she said.

Hard lessons

Ms. John, 61, and her husband of nearly four decades, Phil John,

66, first moved to Paradise in 1989 and raised three children.

Their house, along with a number of others on their street,

escaped the fire, and the Johns returned seven months later.

At work, Ms. John had to figure out how to accommodate the

remaining students in the schools still standing. The plan was to

move elementary-school students to the middle school, and

middle-school students to Paradise High, where she had previously

worked as principal.

Before reopening, the district's four surviving campuses needed

a large-scale cleanup, and two of the schools needed new paint,

furniture, white boards, computers and other electronics.

The couple's house also needed gutting. As Mr. John, a Vietnam

veteran, and his wife worked to restore the house over the months,

they found spots dusted with ash in drawers and cupboards, still

smelling of smoke.

The Johns installed a filtration system for laundry, washing

dishes and showering. For cooking and drinking, they bought cases

of bottled water.

Daily life in a near-empty town hadn't been easy.

"I don't want to complain because I have a home and it's really

nice, but you better schedule eating, right, because there are only

two places that serve food in Paradise now," Mr. John said in late

May. "And don't forget to go to the store because it closes

early."

He had spent years trying to prevent a fire tragedy and felt a

measure of guilt. Mr. John volunteered on the Paradise Ridge Fire

Safe Council for roughly a decade. Over the years, he spoke

regularly to neighborhood groups about ways to reduce fire risk at

their homes and properties.

For children, he played a furry, red-vested fire-prevention

character, Ready Raccoon. He performed original raps in costume

about fire safety.

Mr. John helped create Ready Raccoon in 2008, the year wildfires

across Butte County burned 60,000 acres and destroyed or damaged

200 homes. The Humboldt Fire that June imperiled Paradise, and

three of the town's four evacuation routes were closed by fire and

smoke. Fleeing residents were stuck on the road for hours.

"I said over and over again 2008 was a hint," Mr. John said.

"It's not a matter of if, it's a matter of when."

The 2017 Tubbs Fire ripped through parts of Santa Rosa, 150

miles south, and afterward, the Paradise Ridge Fire Safe Council

added evacuation preparedness to their presentations.

After the Camp Fire, Mr. John helped scour through the wreckage

and was shaken after seeing a badly burned body.

"My guts are torn up because I gave my whole life to teach

people what to do and it just didn't work," he said, his voice

choking up.

Sparks of anger

State fire investigators determined the Camp Fire was ignited

when a wire snapped free of a PG&E transmission line near the

town of Pulga, west of Paradise, and the utility has acknowledged

the finding. The Wall Street Journal reported that for years the

utility had delayed an overhaul of that line.

Anger at PG&E erupted in early June during a bus tour of

Paradise by a group of mostly new PG&E directors and CEO Bill

Johnson. The federal judge in charge of overseeing PG&E's

criminal probation from a 2010 gas pipe explosion in San Bruno,

ordered the tour and accompanied the group.

During the trip, the directors watched videos from the fire,

including one of a father trying to reassure his son that they

wouldn't die. They also listened to a 911 recording from a family

trapped in a house.

Steve Bertagna, then a Paradise police sergeant, said he felt

disgusted when it was his turn to address the PG&E

directors.

"What in the hell have you done to us and what are you going to

do to make it right?" he said. "You killed 85 people."

Ms. John, the schools superintendent, also spoke. "Somewhere,

somehow someone knew that this equipment needed to be updated and

they didn't. You ruined thousands of lives" she told the PG&E

directors.

"We obviously acknowledge that our equipment was the cause of

the fire and there's nothing we can say that will change that,"

said Aaron Johnson, a PG&E vice president overseeing the

installation of underground power lines and building electrical

equipment. Nearly 90 PG&E employees also lost homes.

Reflecting local anger, the company reported that some of the

utility workers in Paradise have been harassed and targeted by

anti-PG&E graffiti over the past months.

The utility has said it could take as long as a decade to

improve its electric system across PG&E's 70,000 square-mile

service territory in Northern and Central California enough to

significantly reduce intentional blackouts. The blackouts are done

to lower the risk of equipment sparking wildfires during high winds

and dry conditions.

PG&E, which cut power to more than 700,000 customers earlier

this month, said it would work to make the blackouts smaller and

less frequent.

House and home

In mid-July, Victoria and Travis Sinclaire loaded as much as

they could into their cars and a moving van, and drove from a

rental in Chico, Calif., back to their house on Forest Lane, about

18 miles away. Theirs was the first home rebuilt after the

fire.

"I want to move in right freakin' now," Ms. Sinclaire said,

hours after receiving the certificate of occupancy, opening the

door for their return to Paradise.

The Sinclaires were in such a rush to get home they forgot to

pack sheets and a comforter. On their first night, they slept under

towels on an air mattress. The next day, Ms. Sinclaire, a

39-year-old county social worker, sat in her new recliner,

delivered hours earlier, and admired her new living room set.

She and her husband were lucky. Ms. Sinclaire worked part time

as a bookkeeper for Ken Blanton, owner of Integrity Builders. He

and his crew did the work. Mr. Blanton, a Paradise resident, said

that days after the fire he sat in a hotel already anxious to begin

restoring the town.

"I knew my part would come in rebuilding," he said. His house on

South Libby Road was the seventh of the nine rebuilt in Paradise so

far. His team is working on nine more.

The Sinclaires' return was costly. Insurance covered about 75%

of the value of the burned house and its contents. They had paid

$180,000 for their old three-bedroom with a white picket fence out

front.

They borrowed to build their new house, which has an extra

office nook, and the addition of fire sprinklers and fire-resistant

siding.

Ms. Sinclaire said that even with the headaches of construction,

it was cathartic. She had returned to work three weeks after the

fire, and the stress of helping other survivors, while facing her

own trauma, prompted her to take a leave at the end of April. Her

doctor put her on antianxiety medication.

Rebuilding returned a sense of agency she had lost in the fire.

She focused on things in her control: picking out tile for the

bathrooms and handles for kitchen cabinets, deciding on purplish

gray paint for the great room.

Her return home hasn't erased her fears from the dry, windy

November day a year ago. She had noticed the fire on the town's

horizon early that morning. Shortly after arriving at work, she

realized it had moved dangerously close.

She called her mother and headed home. An evacuation alert hit

her phone as she pulled into her driveway. "We've got to go," Ms.

Sinclaire called to her husband and their daughter, Emily.

Mr. Sinclaire, a Safeway grocery store employee, and Emily, a

senior at Paradise High, drove one car, Ms. Sinclaire drove

another. As they left, she saw fire at a neighbor's house a couple

of doors away.

She broke off from her husband and daughter to head for the

Sherwood Forest Mobile Home Park for her grandmother. Some of the

mobile homes were on fire when she arrived.

Her husband and daughter kept in touch by phone. When they

passed the Safeway and McDonald's, they reported that the buildings

were safe. When Ms. Sinclaire and her grandmother drove by minutes

later, they were burning.

Planes buzzed overhead dropping fire retardant. A tree exploded

from the heat as they drove past. Their escape took more than six

hours. "I don't know how we lived through it," Ms. Sinclaire

said.

In December, Ms. Sinclaire dug through the ashes of her house.

She found her great-grandmother's teapot, unbroken, a vase her

mother made in seventh grade and a tiny blue cup from her

daughter's first tea set.

She lamented losing the American flag that had draped her

father's casket and the snow globes and magnets she had bought as

mementos of family trips. Despite lingering trepidation, Ms.

Sinclaire felt the urge to return to Paradise. "I still felt at

home even though everything was in shambles," she said.

Months later, Ms. Sinclaire puttered around her new kitchen,

setting up the coffee machine, unpacking dishes. A wall hanging

read, "Family gathers here."

She strolled her freshly laid front lawn and stared up at the

few trees still on her lot, enjoying the pine-scented air and the

quiet.

Without any neighbors yet on their block, Mr. Sinclaire worried

about being isolated at night. A squatter was living on a burned

lot down the street.

"Is someone going to break in?" Mr. Sinclaire said. By

mid-August, construction had begun on the house next door.

Ms. Sinclaire confessed to moments of panic on hot, windy

days.

"Am I afraid there might be a fire? Yes," she said. "Sometimes,

I'm like, 'We can't do this.' "

Protect and serve

Earlier this year, Paradise Police Chief Eric Reinbold drove his

beige Crown Victoria through neighborhoods he had known his whole

life.

"Everything that I used to know and grew up knowing and seeing,

it no longer exists," the 36-year-old chief said.

As he pulled into Ron's Wheel and Brake on Clark Road, he

gestured toward the residential lot at the back of the property.

Metal chair frames were all that remained of what was once his

grandmother's house.

"I spent my childhood there," Mr. Reinbold said. It reminded him

of times spent as a boy with his father. The Camp Fire consumed

every house he had lived in, he said: "It kind of strips you of the

memories."

After the fire, Mr. Reinbold, his wife and their three children

moved between apartments in Chico, about a 30-minute drive from

Paradise. He had first thought about rebuilding the home in town he

bought in 2017.

The 6-acre property had room for his children to ride dirt bikes

and see deer and wild turkeys roam. Their three-bedroom, two-story

house was gone. All that survived was a 2,400 square-foot steel

workshop that Mr. Reinbold had finished building a couple of weeks

before the blaze.

Then came a notice from the California Department of Insurance:

His carrier, Merced Property & Casualty Co., was being taken

over by state regulators. The California Insurance Guarantee

Association, which has statutory limits on coverage, would pay

about $85,000 less than the cost to rebuild.

Early in January, state and local authorities announced that

benzene levels in the water made it potentially unsafe to drink or

cook with. Mr. Reinbold figured it would cost as much as $50,000 to

drill a well.

The price of returning home was too high. In May, he and his

wife bought a house in Chico, one of the many places where Paradise

residents relocated.

They still haven't figured out what to do with their Paradise

property. He hasn't found a major insurance company willing to sell

him more than liability coverage. That has him worried about other

residents who are deciding whether or not to return.

"When you talk about what's going to bring families back and

stuff, well what do families look for?" he said. "They look for a

nice place to live and they want to make sure their kids are going

to be in an education system that is thriving."

In July, Mr. Reinbold sat in his office wondering how many

officers he would need to protect the town when he didn't know how

big a population the department would serve in coming years. The

town council had approved hiring bonuses to attract new officers,

but his staff continues to shrink.

There are fewer calls for police, though they include the same

small-town offenses as always: theft, illegal drugs, driving under

the influence.

The police department has turned over nearly all the local 911

duties to the Butte County Sheriff's Office. Mr. Reinbold told the

town council he wasn't sure when the population would again support

its own dispatch operation.

Mr. Reinbold also frets about what happens if one of his

officers is badly hurt while on patrol. The closest hospital trauma

center is now in Chico.

A new tragedy

In late May, Mr. John was supporting proposed fire safety

regulations for homes in Paradise. The community divided over the

measures because they could add to rebuilding costs.

"People up here being independent thinkers don't think

government should tell them they should spend more money to make

their houses more fire safe," he said a few weeks before the June

11 meeting on the proposals. "I'm telling them, 'Because you're my

friend and I like you, I want you to do it.' "

The Johns planned a short getaway ahead of the town council

meeting. Ms. John was going to Reno, Nev., with her daughter and a

cousin. Mr. John headed to a 40-mile bike race in Ukiah, Calif.

As he left the house, Ms. John joked, "Don't get hit by a

car."

"Don't put me on a machine if I do," he said.

Ms. John got a call the next day saying her husband, Papi to

their grandchildren, had suffered a heart attack as he neared the

end of the ride. Two days later, Mr. John died.

That evening, the council opened its meeting with a moment of

silence in his honor before hearing more than two hours of

testimony from residents over the proposed fire safety

measures.

Ms. John put the school district in the hands of two assistant

superintendents. During her mourning, she tried to work at least an

hour a day.

"My line used to be, 'What's best for the kids?' " she said.

"And now it's, 'What would Phil want me to do?' "

Before the new school year started, Ms. John anticipated that

about half the staff would return. Neighboring districts had hired

many of the Paradise teachers to accommodate an influx of students

from families displaced by the fire.

On the day before the start of school, Ms. John thanked the

teachers gathered for her address: "I get out of bed and go on

living because of all of you."

The next day, Ms. John stood in the gym at Paradise High,

watching students leave the bleachers after a rally. Nearly 1,800

students returned to the district for the new school year, about

half of last year's total.

"So many kids," she said; 262 teachers and staff also arrived on

the first day of school, compared with 400 last year.

In late September, Ms. John announced her retirement, saying she

would step down as superintendent on Dec. 3.

"What we have all been through together this past year are

experiences that no other district in history has had to endure.

And yet we have persevered," she wrote to the school board. "It is

now time for me to go be with my children and grandchildren."

Last week, Ms. John signed escrow papers on the sale of the

house she shared with her husband for 13 years. She wants to live

closer to her grandchildren, somewhere outside of Paradise.

Open for business

In early June, Lok Keobouahom watched over a handful of

customers having an early dinner at his restaurant, Sophia's Thai

Cuisine.

He moved around the restaurant chatting and laughing with

customers. His twin 10-year-old daughters, Maya and Polly, sat

drawing at a table.

Mr. Keobouahom's restaurant and the family's house next door

survived the Camp Fire. Now, he wondered what would happen after

the many utility workers and cleanup crews left town. Even with

those steady customers, business was only about 40% of normal.

"My daughters, they say, 'Let's move away, Dad,' " he said.

"They got no friends here."

The 48-year-old restaurant owner came to the U.S. from Laos in

1990. He moved to Paradise 14 years ago to work in his aunt's

restaurant. He and his wife, Khek, bought the business in 2008.

Paradise was now home.

After officials declared the town's water supply unsafe, the

restaurant owner brainstormed with managers of the local Starbucks

and Save Mart grocery.

Mr. Keobouahom had a large gray tank installed outside the

restaurant's front entrance and set up a monthly order for 2,000

gallons from a water trucking company. On Feb. 8, Sophia's became

the first full-service restaurant to reopen.

"Sometimes, I feel like what am I doing here? Why don't I run

away like everybody else?" Mr. Keobouahom said.

The start of school sneaked up on the family. When a visitor

mentioned the first day of school, the twins, who turned 11 over

the summer, turned to stare in surprise at their father.

The next day, Mr. Keobouahom and his daughters were among the

families bound for the newly renamed Paradise Ridge Elementary.

"I have butterflies inside," Maya said.

At the entrance, the twins saw their class assignments on paper

lists posted on easels and then ran off to find friends.

Write to Erin Ailworth at Erin.Ailworth@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

October 21, 2019 11:03 ET (15:03 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

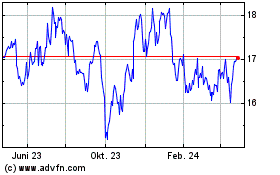

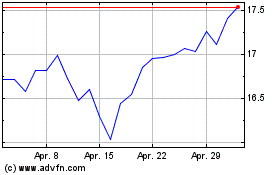

PG&E (NYSE:PCG)

Historical Stock Chart

Von Mär 2024 bis Apr 2024

PG&E (NYSE:PCG)

Historical Stock Chart

Von Apr 2023 bis Apr 2024