By Erich Schwartzel

LOS ANGELES -- About two years ago, employees who managed Walt

Disney Co.'s princess characters gathered to watch an extended

scene from an unreleased movie.

The executives had spent years cultivating Ariel, Elsa and Snow

White as highly profitable models of femininity. The footage they

saw, from this month's animated feature "Ralph Breaks the

Internet," revealed the princesses as everyday young women, on

break from their jobs as Disney royalty.

Elsa and Sleeping Beauty have their hair down and wear pajamas.

Snow White shows off her Coke-bottle glasses. Cinderella shatters

her glass slipper and thrusts it forward like a broken bottle at a

girl who walks into the room. Rapunzel asks her, "Do people assume

all your problems get solved because a big, strong man showed

up?"

"Everyone audibly gasped," according to a person present. In

their eyes, the scene broke all of the Disney rules that had built

the princesses into a lucrative brand.

For nearly 20 years, Disney employees have debated how far the

company should go in updating its heroines for the modern age. The

crux: How do you keep princesses relevant without alienating fans

who hold fast to the versions they grew up with? Billions of

dollars of revenue -- dolls, sequels, stage shows and dresses --

hang on getting that balance right.

Since "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" in 1937, the princess

characters have trained generations of young moviegoers on men,

women, relationships and love. The franchise, especially its older

films, has been criticized for promoting outdated notions of

femininity and damsel-in-distress narratives in which only a man

can save the day.

Parents are wrestling with the messages the stories send their

children -- is it acceptable for the prince to kiss Sleeping

Beauty, given she's sleeping? The tension has grown more pronounced

in an era of female presidential candidates, women's marches and

#MeToo.

Disney develops and manages characters such as Mulan or Rapunzel

similar to the way Apple Inc. handles new iPhone models, with a

secretive process that allows the princesses to debut in public

fully formed. Interviews with nearly two dozen current and former

employees working across Disney's sprawling princess operations

reveal a perennial push-and-pull over getting the mix of tradition

and modernity right, from producing remakes and merchandise built

around longtime characters to introducing new characters.

"They've tried to make the princesses more independent and to

have more of a voice, but at the same time there's a recognition

that there's also an appeal -- even if it's not as modern -- to

pretty dresses and beautiful castles," said one former Disney

executive.

Disney declined to make executives available for an

interview.

More than 80 years after "Snow White" hit theaters, Disney still

sells figurines, Grumpy costumes and themed Play-Doh sets. "Frozen"

has become one of Disney's greatest hits, spawning a sequel, a

Broadway adaptation and countless "Let It Go" downloads since it

hit theaters five years ago. The live-action remake of "Beauty and

the Beast" collected $1.26 billion at the global box office in

2017.

Employees who work on the princess brand -- they can number in

the hundreds when a new movie is in production, with groups across

consumer products, parks, animation and television -- try to find

the right balance that will resonate with the largest number of

fans. Hundred-page manifestos outlining the colors, language and

attitude that licensees and designers should use for each princess

are treated as gospel. Data is mined from sources ranging from

academic studies to toddler focus groups at the company's campus in

Burbank, Calif.

The characters have grown more complex over the years. That

hasn't prevented debates from forming in recent years over princess

outfits, live-action updates and the word "princess" itself.

"No matter how hard you try, a 4-year-old girl is going to want

to be a Little Mermaid," said one former Disney executive. "But if

they try to make Ariel into a lawyer, there's going to be a huge

backlash."

Disney's efforts must resonate with consumers like Lesley

Godbey, a 31-year-old mother of two in San Diego.

Ms. Godbey's daughters worship the Disney princesses, much like

she did growing up with Ariel and Belle in the 1990s. She even

dresses as Belle at fan conventions, posing for photos in the

character's signature canary-yellow dress.

When she's reading princess stories to her daughters, she also

wants them to know there's more to life than the fairy-tale

telling, so she has taught them a call-and-response.

If a story ends with "And they lived happily ever after," her

daughters chime in, "with lots of hard work and open

communication!"

kkk

After the "Ralph Breaks the Internet" screening, executives

worried that too many toys and apparel around the edgier version of

the princesses could overshadow the traditional representations,

according to a person familiar with the matter.

Retailers expressed interest in princess dolls and clothes

pegged to the "Ralph" release, this person said. Disney put

together some merchandise, including a doll set featuring the

princesses in everyday clothes as well as shirts for young girls

modeled after the princesses' pajamas. After fans embraced the

scene, some Disney executives questioned why they hadn't pushed

even more product around it.

The movie's filmmakers had a crucial ally for the updated

portrayal: former chief creative officer John Lasseter, who had

long wanted to bring the princesses down to earth, colleagues say.

Mr. Lasseter had received approval and support for the scene from

Disney Chief Executive Robert Iger, the CEO, according to people

familiar with the matter.

"If I were to make the movies you guys wanted me to make about

princesses, I would be murdered," Mr. Lasseter once told a group

raising concerns about the character Merida's cynical attitude in

"Brave," according to a former colleague. He said, "I couldn't make

the movies Walt Disney made today."

Mr. Lasseter couldn't be reached for comment. He left Disney

earlier this year following allegations he had inappropriately

touched subordinates. After the allegations surfaced, he sent a

letter to employees apologizing to "anyone who has ever been on the

receiving end of an unwanted hug or any other gesture."

His successors, Pete Docter at Pixar and Jennifer Lee at Disney

Animation, have strong track records of strong female characters in

movies such as "Inside Out" and "Frozen."

Among Disney's imminent tests: A sequel to "Frozen" is slated

for next year, and a small group of fans have called for a lesbian

love interest for Elsa. Live-action remakes of "Aladdin" and

"Mulan" are in the works. At Disney, and the industry in general,

sales of toys tied to movie releases have fallen in recent years,

putting more pressure on the princess team to sell dolls and

dresses.

Meanwhile, new role models, such as Rey, the lightsaber-wielding

protagonist of the Disney "Star Wars" features, have won over young

girls. The Disney television shows "Elena of Avalor" and "Sofia the

First" portray more independent heroines.

In October, actress Kristen Bell -- the voice of Anna in

"Frozen" -- told Parents magazine she dissects the older princess

narratives with her daughters.

"Don't you think it's weird that the prince kisses Snow White

without her permission?" she said.

Keira Knightley, a star of Disney's recent "The Nutcracker and

the Four Realms," said last month on "The Ellen DeGeneres Show"

that she's kept "The Little Mermaid" from her home because of

Ariel's decision to forfeit her voice to find love: "I mean, the

songs are great, but do not give your voice up for a man.

Hello?!"

Melissa Villaneuva, a 28-year-old mother of two in Los Angeles,

said her mother would show her movies like "The Little Mermaid" and

"Snow White" and tell her, as the credits rolled, "You have to find

someone to take care of you."

Movie nights with her son and daughter, ages 11 and 10, now

feature more empowered narratives like "Tangled" and "Brave."

"I don't want them to think like I did," Ms. Villaneuva

said.

kkk

The modern Disney princess business dates to 2000, when a

company executive named Andy Mooney attended a Disney on Ice show

in Phoenix. He found himself surrounded by young girls in homemade

princess costumes.

Why couldn't they buy such a dress at a Disney store? he

thought, according to published interviews. Mr. Mooney declined to

comment.

Until that point, merchandising for older Disney princesses went

on sale only if it was part of a coming movie's campaign. Mr.

Mooney's idea: Build a franchise that sells toys and dresses and

books about classic characters like Snow White and Cinderella along

with newer heroines such as Ariel and Belle.

In 2000, sales for the princess division were worth $300

million. By 2009, they had reached $4 billion, Disney says.

The new concept came with a crucial rule, invisible to most

everyday fans, that is still practiced by princess purists at

Disney today, employees say.

Animators must draw princesses' eyes looking in different

directions when they appear on the same lunch box or poster. That's

because the princesses are not to live in the same imagined

universe, even if they're adjacent to each other in the physical

world.

"Ariel and Belle wouldn't be friends. Cinderella and Snow White

wouldn't know each other," said one former Disney executive.

That rule was thrown out the window with the scene in "Ralph

Breaks the Internet" -- and breaking it was a major reason behind

some employees' consternation.

For several years following its creation, Disney's princess

franchise worked with both classic and modern characters, such as

Belle, known for her bookishness, and Mulan, the Asian warrior

princess. Remakes and merchandise related to the classic characters

renewed criticism of the old-fashioned narratives.

In 2009, Disney released "The Princess and the Frog," its first

animated princess movie in more than a decade, starring Tiana, the

company's first African-American heroine. It grossed a

disappointing $104 million at the box office. It remains the

company's lowest-grossing princess movie.

Tiana's introduction was a breakthrough, but the movie's

performance had the princess workers worried the word "princess"

itself was a liability.

With budgets for animated movies often approaching $200 million,

Disney needs to appeal to a range of young moviegoers to achieve

the blockbuster grosses that ensure profitability. The word

"princess," they worried, alienated boys.

The next year, a princess movie about the long-haired Rapunzel

was called "Tangled." Two years after that, a movie about Merida,

the pugnacious redhead princess was titled "Brave."

Sometimes the company's other attempts to steer away from the

girlier aspects of princesses backfired among some employees.

Before the release of "Frozen" in 2013, some consumer-products

executives thought moviegoers -- and specifically boys -- would

respond to Olaf, the goofy snowman sidekick of the film, people

familiar with the matter said. Mr. Lasseter didn't want the movie's

marketing to focus too much on the sisters and risk being written

off as just another princess movie, his former colleagues said.

For some Disney employees, Elsa and Anna embodied just the kind

of message they wanted to send -- only to see higher-ups play it

down for fear of alienating boys.

"The creative side has leeway and scope. And then there is this

massive, unwieldy side dictated by middle management that can

really dumb up the machinery, which is why you can have a

progressive film like 'Frozen' but then see that the company

focuses consumer products on Olaf," said one former Disney

executive who worked on the princess brand.

Olaf ultimately took a small role in a consumer products

campaign centered on the princesses, and stores still ran out of

dolls and dresses inspired by Elsa, the movie's strong-willed

heroine. "Frozen" collected $1.28 billion at the world-wide box

office.

Soon after "Frozen" came the adaptation of "Cinderella," the

first of several planned live-action updates to older titles. These

modern-day versions, employees say, forced Disney to look at its

classic characters with fresh eyes.

The prince in the 1950 "Cinderella" original has only six lines

of dialogue -- two of which are, "Wait!" Chris Weitz, writer of the

2015 live-action version, wanted to deepen the prince's character

to make him "worth Cinderella's attention." He said, "Cinderella

is, in a way, the most regressive fantasy of the Disney princess.

If you were just to read it, it says what you need to save you is a

handsome and wealthy man -- who in fact she doesn't know very

well."

Sections of dialogue were added to the 2017 live-action "Beauty

and the Beast" to contend with what director Bill Condon called the

"Stockholm syndrome" of a story about a young woman who falls in

love with her captor. Mr. Condon said he was pushed by Emma Watson,

the 28-year-old actress playing Belle, to include dialogue that

showed her resistance:

Beast: You think you could be happy here?

Belle: Can anybody be happy if they're not free?

The live-action "Aladdin," due for release in May, elevates the

role of Jasmine from the cartoon version, where she was often

secondary to Aladdin's antics. A live-action "Mulan," currently in

production for a 2020 release, features Chinese actress Liu Yifei

leading an Asian cast in the story of a young woman who disguises

herself as a man to join in a battle.

Even modern-day princesses have caused problems after they have

left theaters. Merida of "Brave," for instance, was considered "too

thick" in girth by some employees when the movie was first

conceived, according to employees. The argument was eventually

overruled.

In 2013, still selling figurines and posters of Merida a year

after the movie's release, Disney released a new image of the

character. The update, marking her official coronation as a Disney

princess, gave her a cinched waist and cleavage.

After fan outcry over the slimmer, glammed-up Merida, Disney

returned to the original version. For months afterward, employees

say, confused designers wondered: "Which version of Merida are we

using?"

The next test will come soon enough with "Ralph Breaks the

Internet." In the summer of 2017, Disney showed the princess clip

that had divided its own employees at an annual gathering of

die-hard fans, some dressed as princesses themselves.

The audience burst into applause.

Write to Erich Schwartzel at erich.schwartzel@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

November 17, 2018 00:14 ET (05:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

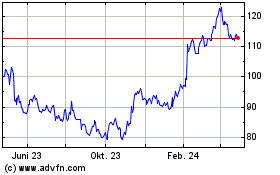

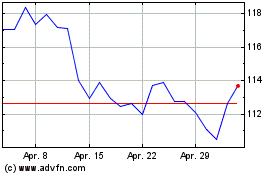

Walt Disney (NYSE:DIS)

Historical Stock Chart

Von Mär 2024 bis Apr 2024

Walt Disney (NYSE:DIS)

Historical Stock Chart

Von Apr 2023 bis Apr 2024